...in 1997, Nicolaisen decided to participate with a parasitic project. He went to Münster, found an appropriate exhibition space in a pavilion, produced a catalogue, posters, postcards and a press release and attended the official press conference. In short, he acted as if he were part of the Sculpture Project Münster. His actions were fuelled by impatience, a feeling of not wanting to wait until he was seventy....

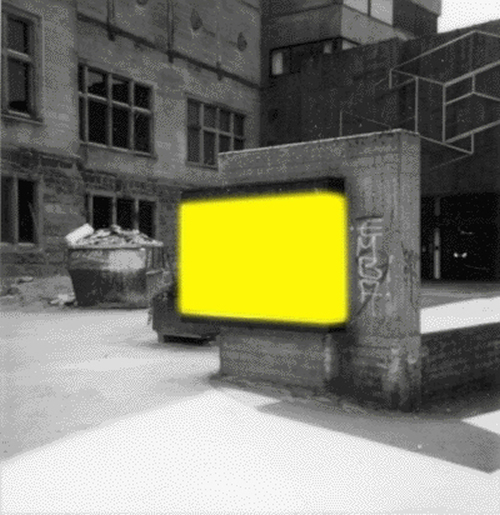

But whereas Peter Weibel and Michael Asher emptied the space in order to show the gallery as an architectural framing device, Nicolaisen chose a different strategy to objectivise the space. The gallery itself was closed to the public during the exhibition and could only be seen from outside. In this way, the gallery was transformed from a venue for socialising and experiencing art to an inaccessible sphere that only emitted an enigmatic, yellow light.

Ingvild Krogvik

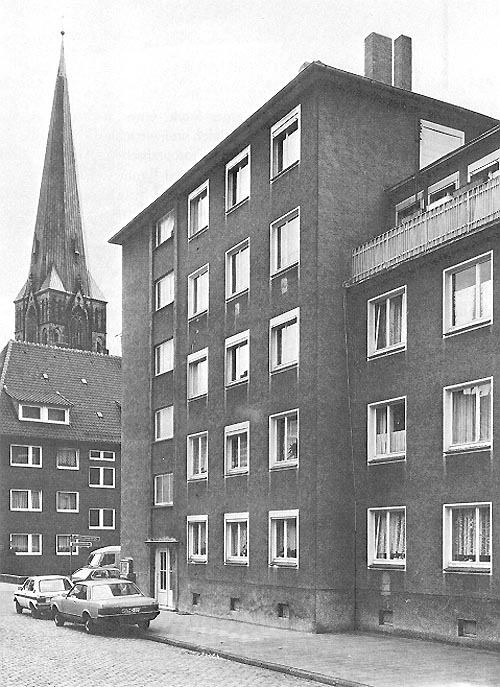

(...) However, Nicolaisen’s curiosity about the proposal genre was not triggered by Lawrence Weiner or Joseph Beuys, but by two discoveries: the first was the catalogue for Sculpture. Projects in Münster 1987, which he came across by chance at the end of the 80s. The exhibition, which Nicolaisen never witnessed himself, consisted of sculptural works erected in public places in Münster. But he studied the catalogue in detail. Produced in good time prior to the exhibition, the catalogue contained texts, illustrations in the form of photographs and working drawings of planned projects. Several of the catalogued projects were illustrated by means of photographic montages and it was in some cases impossible to determine whether the work had actually been produced or not. This uncertainty made Nicolaisen realise that it did not really matter one way or the other. The works in the catalogue had just as strong an effect, whether they had been realised or not. (...)

Ingvild Krogvik, Utopia As A Critical Tool, Supplementary Notes 1994 - 2011 on Selected Proposals 1995 - 2002, Henie Onstad Art Centre 2011

(...) None of Nicolaisen’s Oslo projects have been realised in practice. However, some of them have been realised within the confines of art institutions – usually on invitation, but sometimes also without invitation. Parallelle Projekte in der Stadt Münster 1997 is an example of the latter. The catalogue from the exhibition at Münster in 1987 had played an important role in Nicolaisen’s formative years and when the exhibition was again to be held ten years later, in 1997, Nicolaisen decided to participate with a parasitic project. He went to Münster, found an appropriate exhibition space in a pavilion, produced a catalogue, posters, postcards and a press release and attended the official press conference. In short, he acted as if he were part of the Sculpture Project Münster. His actions were fuelled by impatience, a feeling of not wanting to wait until he was seventy.

But Nicolaisen’s intervention also had a more principle aspect to it; it could be seen as a criticism of the regulatory role of the art institution – a role stemming not only from ideas of “quality” and “topicality”, but also from the intention to “reward”. This idea lies behind retrospective exhibitions, but it is also present at biennials like that in Münster where “deserving” artists are invited to exhibit their works after long carriers as artists.

The work that Nicolaisen presented at Münster was part of a larger project entitled Yellow Light, which had been shown at a number of venues. It was the first of a long series of works by Nicolaisen that comments on the art institution. The project involved emptying the gallery space of art objects and replacing them with an intense, yellow light. Nicolaisen’s use of gallery space had predecessors in conceptual art from the end of the 1960s to the middle of the ‘70s.

During this period, artists such as Mel Bochner, Marcel Broodthaers, Peter Weibel, Hans Haacke and Michael Asher began criticising the institutional contexts art operated in. This marked the beginning of the practices that were later to be called institutional critique. Many of these early works aimed to show how the white cube, with its white walls, artificial lighting and shuttered windows, contributed to separate art from the real world. The idea was that the white cube upheld Modernism’s dogma about the autonomy of the work of art.

Yellow Light was produced three decades later, at a time when the Modernist discourse on art’s autonomy discourse was more or less irrelevant. But the point of departure for the series was nevertheless an “anti-white-cube attitude”. Nicolaisen later explained the motivation behind the project:

It seemed to me […] that whatever you put into

a White Cube, would function as art. This led to

the assumption that the white cube itself is

the genuine artpiece and that this space

is the object and the art it’s hostage!

In Yellow Light, the gallery itself was turned into a readymade, as Peter Weibel, Michael Asher and others had done in the early days of institutional critique. But whereas Weibel and Asher emptied the space in order to show the gallery as an architectural framing device, Nicolaisen chose a different strategy to objectivise the space. The gallery itself was closed to the public during the exhibition and could only be seen from outside. In this way, the gallery was transformed from a venue for socialising and experiencing art to an inaccessible sphere that only emitted an enigmatic, yellow light.

For those unfamiliar with Nicolaisen’s projects, the work appeared merely as a yellow light shining from a room. One of the core ideas of Nicolaisen’s oeuvre has been precisely that of creating a non-artistic room around his own works. The works are often “unrecognisable as art” and appear to be, for example, urban spaces or sites. Nicolaisen’s intent was to capture the attention of the viewer “without him having to navigate through an understanding of art […] Freed from this particularly problematic and mystical understanding, the beholder has related to the art work on a 1:1 basis, through an open and average degree of interest. In this context, art has been revived, albeit without identity.” (...)

Ingvild Krogvik, Utopia As A Critical Tool, Supplementary Notes 1994 - 2011 on Selected Proposals 1995 - 2002, Henie Onstad Art Centre 2011

_______________

Strategy, absurdity and restless comments excerpts

Tina Rigby Hanssen

It is still Conceptual art from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s that most clearly sets the premise for Nicolaisen’s artistic practice. First of all, the movement’s insistence on ideas rather than visuals as the foundation for the works’ content, but also its anti-monumental approach to sculpture – an approach that showed a penchant for transitory materials such as soil, water, felt and asphalt rather than traditional materials such as marble, stone and bronze.

One of the inspirations for Nicolaisen’s work with proposals is the American conceptual artist Michael Asher’s institutionally-critical works. (1) Asher presented a number of suggestions for physical changes at museums and galleries, and several of these were realised. In 1970, he proposed, among other things, that the Pomona College Museum of Art should remove all its entrance doors, a physical intervention that resulted in the gallery being open day and night over the course of the exhibition period. In 1974, he suggested to Claire S. Copley Gallery in Los Angeles to remove the wall that separated the exhibition room from the employees’ office. This physical intervention made the office part of the exhibition space so that visitors gained full insight into the business’ daily routines and tasks.

Nicolaisen’s Gult lys (1994-1998, Yellow Light) can be seen as a continuation of Asher’s works. Gult lys was shown, amongst other places, in Münster in 1997 at the same time as the execution of Skulptur. Projekte in Münster 1997. Nicolaisen was not invited to participate in the exhibition programme, but chose to conduct his own intervention in the exhibition and in the city by presenting a self-produced exhibition with a catalogue, poster, postcards and press release. The work itself was to empty the gallery space of artworks and fill it with an intense, yellow light. Nicolaisen also went to the drastic step of shutting the audience out of the gallery space; the audience could only view the yellow light through the windows, standing on the sidewalk outside the gallery room.

1) Krogvig draws up three specific sources of inspiration for Nicolaisen’s work with proposals: the catalogue of Skulptur. Projekte in Münster 1987, where one can find texts, photographic illustrations and working drawings of planned projects for the exhibition; the drawn proposals for monuments to Claes Oldenburg, which show gigantic, imaginary monuments based on trivial everyday objects such as fried eggs, vacuum cleaners and clothes pegs; as well as the institutionally-critical works of artists such as Michael Asher, Mel Bochner and Marcel Broodthaers.

____________________

Nicolaisens omgang med gult lys står i en stilling for seg. På en utstilling i Galleri Otto Plonk i Bergen i 1996 kom publikum til en stengt galleridør. Inne var lokalet derimot fullt opp med et kraftig, gult lys som strålte ut gjennom noen ruter. Kunstverkets objektkarakter og kunstsystemets varefetisjisme ble undergravet samtidig som selve kunstrommet ble løftet frem som kilde til energi og innsikt.

I forbindelse med Skulpturprosjekt Münster året etter «deltok» han med sitt eget «parasittære» prosjekt der tanken var å lyssette forskjellige bygninger i byen på tilsvarende vis. Både byen og den prestisjefylte kunstutstillingen interveneres på en humoristisk, tankevekkende måte. At de fleste ikke lot seg realisere, er av underordnet betydning. Visualisert i tegninger og smalet i egne kunstbøker vitner dette og andre typer urbane eller stedlig forankrede ideer og forslag om et ønske om å injisere byer, steder og situasjoner med lys og farge.

Øystein Ustvedt, En ny oppmerksomhet om tegning i Nyere Norsk Kunst etter 1990

____________________

Postcard to König written on my postcard from the Parallelle Projekte in Münster 1997:

Dr. Kasper König

Office Kasper König

Kurfürstenstrasse 13

10785 Berlin

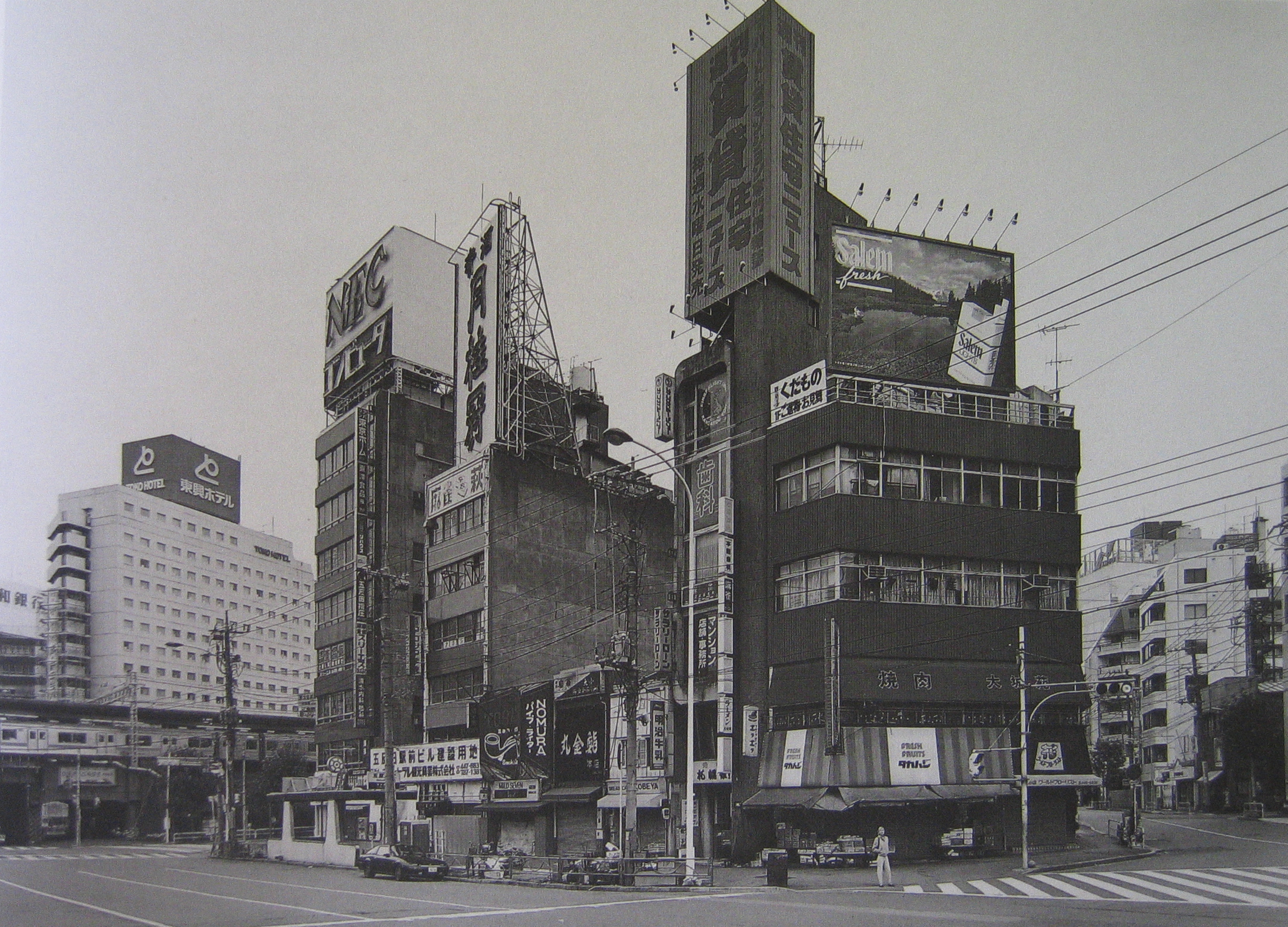

Today I woke up at 05:45. A nice day for a painting. (But not as nice as Wednesday two weeks ago: 11.11.15). I have been walking mostly, taken a few nice shots and re-photographing both the Thomas Struth-locations from 1987 (Nachtprojectionen), in Grevener Strasse, Margareten Strasse and in Wollbecker Strasse. I also re-shot my own locations from 1997. A very narrow and limited project I’m afraid. Nobody I spoke to during my stay here, had heard of SPiM, which I think is rather surprising! It would be a good project to make a city führer for the inhabitants of Münster, something to make them aware and be proud. It had to have both realized and unrealized projects and be un-elitist.

Thank you for initiative

Überwasserhof Wed. 25/11/2015

___________________________

Dagbladet:

:KUNST UTSTILLINGER Dato:5. juli 1997

Tittel: Norsk i Münster Brødtekst:

«Parallellprosjekt» kaller den norske kunstneren Terje Nicolaisen sitt uoffisielle bidrag til Münsters skulpturelle sommer. Han har installert gule lysrør i en sakral arkitektonisk sammenheng ved

berwasserkirchplatz i byens sentrum.

_______________________________

The catalogue / Artist-book from this project can be downloaded from the E-flux archive Agency Of Unrealised Projects

___________________________________

Gypsy Artist or Whatever...

Per Teljer

At Skara Sommarland (a popular tourist attraction in western Sweden where pale Swedes spend a small fortune on making fools of themselves in public with an orgy of beer, fast food, candy floss, go-karting, bungee jumping, water games of various kinds and so on) in the mid 1990s, the owner Bert Karlsson decided that gypsies were to be denied admission to all these wonderful attractions on the grounds that any individual with the slightest drop of Romany blood was a potential kleptomaniac.

Hi Per, I don’t know if you remember that we discussed gypsy tendencies and the like in relation to my work (you said you could see such a thread). Now I’m going to produce a catalogue for a solo exhibition at Tegnerforbundet, and I was wondering if you fancied writing an article about this, as brief or long as you like … Terje Nicolaisen and the gypsy artist or whatever … What do you think, eh? Like the idea? Terje.

E-mail from Terje Nicolaisen, 17 October 2000

“Gypsies” – immediate associations: stout women with moustaches, wrapped up in numerous colourful items of clothing, thin men with thicker moustaches in tailor-made costumes, and owners of big, rusty old Mercedes. In some respects, Terje Nicolaisen would get along well as one of these men – the jargon is there somewhere, albeit only as part of a wider context, but it is entirely conceivable that Terje would find it great fun to climb out of a big Mercedes, close the door and walk a couple of paces before locking it with a habitual touch of the remote control.

Romany folk seem to possess a higher form of pride, a stronger desire to preserve their dignity than in many other Western cultures (not least in Scandinavia). In the case of the men, this dignity usually manifests itself in the aforementioned costume; “the clothes make the man”, as people used to say. This is also something that Terje’s works have often touched upon, albeit normally indirectly, as an aesthetically concealed statement. It may manifest itself, for example, in a desperate effort to arrive at the discount supermarket as elegantly dressed as for a Nobel Prize ceremony, in order to briefly suppress the knowledge that you don’t have the financial means to shop at quality food stores. The plastic bags in the bottom drawer in the kitchen reveal as much about people’s social standing in Scandinavia as the state of their teeth does in other countries.

In the very first work I saw by Terje Nicolaisen (then a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Trondheim), he seized on just this fact (probably without starting with gypsies). The work consisted of a large number of baskets from the RIMI supermarket, arranged in various more or less sculptural situations, ready-mades from the everyday life of the lower classes. He subsequently developed the idea by combining these baskets into simple skeletal structures that people could grab hold of or wear directly on their body. In a series of photographs, he flaps around with these structures on his body, like a loser Icarus who, through a dark suit and RIMI wings, is striving to elevate and raise himself above his true social situation.

Gypsies have always been regarded in Scandinavia as work-shy conmen, swindlers, in much the same way as vagrants. Their allotted place is a second-rate funfair surrounded by an abundance of coloured lights, illuminations flashing in series, colourful clowns and other glass-fibre junk.

We are drawn to the coloured light as instinctively as moths.

In Terje Nicolaisen’s work “Yellow Light for Otto Plonk”, “Yellow Light at Kunstnernes Hus”, “Yellow Light at the Museum of Contemporary Art” and so on, the similarity to the above image is striking. In this work, Terje focuses more on the core idea that anything can be sold if you can persuade the customer that he or she cannot live without this particular product. The work itself consists, in short, of a number of light tubes, painted with oil paint and placed in one or more rooms. The visual effect is most powerful when seen from outside at night. So what is the meaning of this work? I have no desire in this article to bamboozle myself with notions of “space” and other aesthetic reflections – what is more interesting is how these works come to be exhibited. Here too, the strongest side of Nicolaisen’s artistic personality comes to the fore, the role of the businessman or horse-trader who can make the wheel spin round next to nothing. Going a step further, we can clearly see a kind of political statement in this: someone or something is exposed, and it is not Nicolaisen or the onlooker, but the very structure of which we are all part. This work is indispensable in this particular situation, only for you my friend!

I clearly remember a discussion I had with Terje at a party, at the time when these works were beginning to be set up and exhibited in various places, about what was the true meaning of his work. To begin with, the explanation was pretty comprehensive, incorporating numerous completely acceptable theories. However, the longer this discussion continued, with arguments bouncing back and forth, the clearer the true intention became – and when Terje finally put an end to any further debate with a big, hearty laugh and a cry of “Cheers!”, everything suddenly became crystal clear. In essence, it is a question of entrenching an idea and an attitude so skilfully that other people will buy it, warts and all. That, damn it, is no easy task, and many people try it without success, while the majority of those who do manage it do not even have the guts to acknowledge it. This is the situation in which Nicolaisen seems to be most at ease, openly flaunting his sales patter coupled with the laid-back style of a dandy. This can often be perceived as kitschy and slightly vulgar, and indeed, why should it not be? It is this side to Nicolaisen’s artistic personality that does most to encourage associations with the superficial aspects of gypsy culture (i.e. the prejudices we have about it): the costumes, big Mercedes, funfairs and so on.

Nicolaisen seems to have an inbuilt need to provoke and confront those around him with his works and his views on the social rules by which we live our daily lives. With great intensity he presents us with his world of ideas, which can easily prove a source of irritation, and on numerous occasions he has certainly been asking for a punch on the nose, but has got away with it thus far (to my knowledge at least). The great kick comes when he succeeds in making us experience a sense of anticlimax when we have seen through the castle in the air and thereby discovered the criticism of our existence or its meaninglessness: Was that it?

To crown all this, Nicolaisen is a member of the Casio dance band Dekadanse, which bases its entire existence on preprogrammed pop tracks. The band was probably formed more for the chance to parade wearing black suits and Ray-Bans, with slicked-back hair, than out of any desire to present high-quality music. Dekadance performs mainly on ferries to Denmark, at weddings, Christmas parties and other public jamborees, which again fits in with the rest of Nicolaisen’s artistic persona and open attitude. When planning this article, I got in touch with a close friend who, I knew, owned a Christmas CD by Dekadanse, thinking that this would give me further inspiration. So I got chatting to this friend and asked if he had the disc handy, but he merely shook his head and laughed. “No, damn it, I’ve given that one to the charity shop!”

________________________

This is the project I was parasiting on:

Skulptur. Projekte in Münster