Museet for Samtidskunst /

Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst

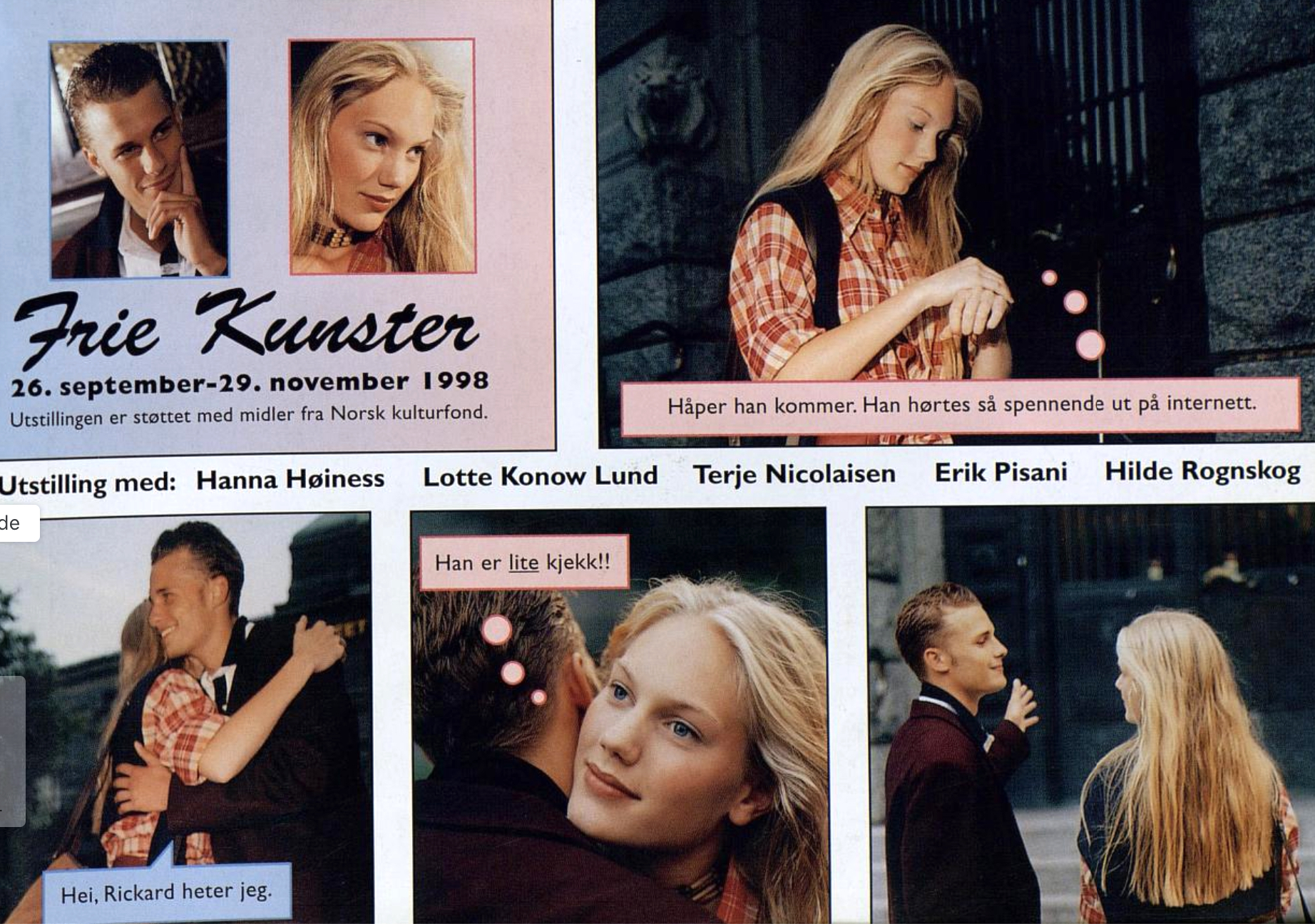

Lotte Konow Lund, Erik Pisani, Hannah Høines, Hilde Rognskog and Terje Nicolaisen

One of the core ideas of Nicolaisen’s oeuvre has been precisely that of creating a non-artistic room around his own works.

Ingvild Krogvik

In this exhibition I installed the last of around 14 Yellow Light installations. I figured, that this was a good peak for this project - that originally was intended as plain institutional critique, but often were interpreted metaphorical. Since the first instalment at Prosjekthallen in Trondheim Art Academy in 1995 this was the final countdown. I was afraid that the poeticical-critical actionism part of the project would be corrupted, should it go any further; museum installations and private collectors could turn this project in to a fetish. I am now the owner of this klische.

Lotte Konow Lund, Erik Pisani, Hannah Høines, Hilde Rognskog and Terje Nicolaisen

A catalogue were released (experimental they call it) and they have this book digitally available, readable > FRIE KUNSTERj Texts by Mari Slaattelid and Tiril Schröder. Curator was Karin Blehr

About the yellow light in general, there was much fuzz, Daniel Ferdman, who was a fellow student, wrote this poetic review in KITSCH 1995:

300 000 km/s Mellow Yellow

Caused by Terje Nicolaisen's installation in the Projecthall at KIT, Trondheim, February 1995

Light is that which makes things visible, and give light to something is to illuminate - to illuminate is to make clear, a help to explain, to make bright - yellow is the colour representing brightness, it expresses energy

- and while it is getting dark outside, I come near to the Projecthall and it becomes clear to me - yellow fluorecent lights have been installed istead of white ones - Terje is creating a field of energy, a powerstation radiating mellow yellow waves of pure illumination to the soul - a metaphor for illumination, in the sense of knowledge of spiritual enlightment?

- but shit, no way into the space, the room is locked - I think Terje gets right to the point here - both thinking about the critical view towards traditional exhibition forms and showing the difficulty of being "illuminated" by art works - the superfluidity of signs without content nowadays makes artworks difficult to grasp: they sink into an ocean of weightless concepts - to develop a codex for communication in our time is an exhausting task

- the room seen as an object illustrates the relationship between seduction and desire: the room seduces us, and blocking the way to the entrance strenghtens the feeling of desire to occupy the space, be a part of a wellknown structure of language on a safe ground

- a sign over the front door produces the same kind of yellow light but is displaying nothing, being as empty as the room - there is no message but the light, connecting with the inside

- that reminds me of illuminating as decoration of public spaces with bright lights as a sign of rejoicing, natural events arranged to give people some kind of unity, some link between them and the social apparatus; and when it is over, everything becomes as dull as before

- public spaces displaying bliss, products loaded with promises about a harmonic existence, but being totally hollow in content, in meaning - brightness is supposed to make people cheerful and happy, to give them hope, light them up with joy - in Terje's installation that does't happen - the doors to happiness are closed, you've been promised something you can't get

- the work is loaded, not with pessimism (as it may sound here), but with a sharp critical comment to the state of things in our society - Terje is not directly political here: he is politically concious leting his work bring up the subject - darkness couldn't have brought up the point so clearly

- I hope we all got enlightened by Terje's work, and as Jean Baudrillard wrote: "...things visible do not come to an end in obscurity and silence - instead they fade into the more visible than visible: obscenity"

- have you seen the light?

_________________________

UTOPIA AS A CRITICAL TOOL excerpts

Ingvild Krogvik (2011)

Published in the book Supplementary Notes 1994 - 2011 on Selected Proposals 1995 - 2005 (2001) Henie Onstad Art Center, Høvik

The work that Nicolaisen presented at Münster was part of a larger project entitled Yellow Light, which had been shown at a number of venues. It was the first of a long series of works by Nicolaisen that comments on the art institution. The project involved emptying the gallery space of art objects and replacing them with an intense, yellow light. Nicolaisen’s use of gallery space had predecessors in conceptual art from the end of the 1960s to the middle of the ‘70s. During this period, artists such as Mel Bochner, Marcel Broodthaers, Peter Weibel, Hans Haacke and Michael Asher began criticising the institutional contexts art operated in. This marked the beginning of the practices that were later to be called institutional critique. Many of these early works aimed to show how the white cube, with its white walls, artificial lighting and shuttered windows, contributed to separate art from the real world. The idea was that the white cube upheld Modernism’s dogma about the autonomy of the work of art.

Yellow Light was produced three decades later, at a time when the Modernist discourse on art’s autonomy discourse was more or less irrelevant. But the point of departure for the series was nevertheless an “anti-white-cube attitude”. Nicolaisen later explained the motivation behind the project:

It seemed to me […] that whatever you put into a white cube would function as art. This led to the assumption that the white cube itself is the genuine art constitution and that the space

is the object and the art it’s hostage. TN

In Yellow Light, the gallery itself was turned into a readymade, as Peter Weibel, Michael Asher and others had done in the early days of institutional critique. But whereas Weibel and Asher emptied the space in order to show the gallery as an architectural framing device, Nicolaisen chose a different strategy to objectivise the space. The gallery itself was closed to the public during the exhibition and could only be seen from outside. In this way, the gallery was transformed from a venue for socialising and experiencing art to an inaccessible sphere that only emitted an enigmatic, yellow light.

For those unfamiliar with Nicolaisen’s projects, the work appeared merely as a yellow light shining from a room. One of the core ideas of Nicolaisen’s oeuvre has been precisely that of creating a non-artistic room around his own works. The works are often “unrecognisable as art” and appear to be, for example, urban spaces or sites. Nicolaisen’s intent was to capture the attention of the viewer

“without him having to navigate through an understanding of art […] Freed from this particularly problematic and mystical understanding, the beholder has related to the art work on a 1:1 basis, through an open and average degree of interest. In this context, art has been revived, albeit without identity.” TN

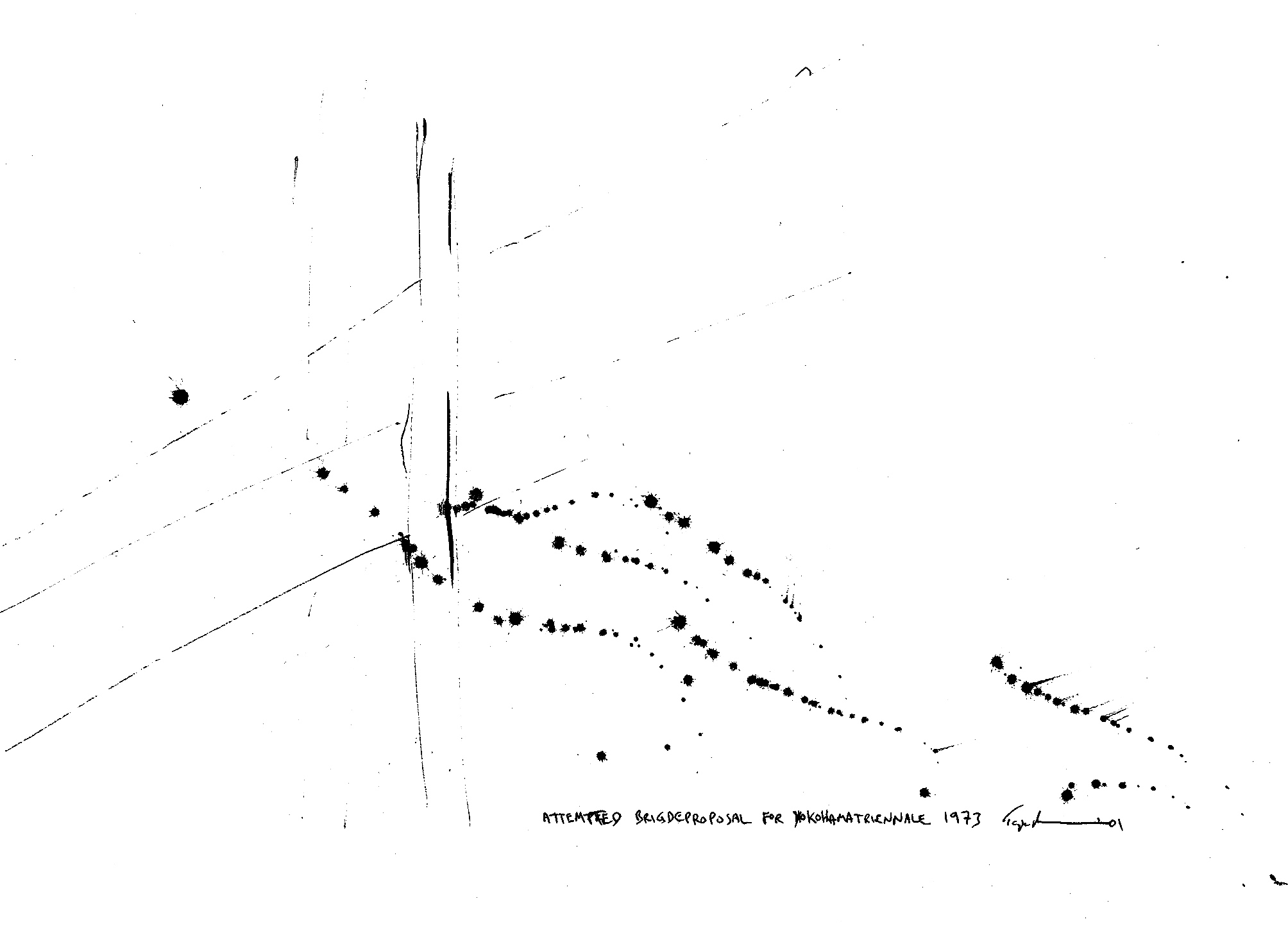

Another example of Nicolaisen’s ability to project himself in contexts he is not a part of is Yokohama Triennale 1973. This proposal is simple enough: “To send a proposal to a triennial that already took place years ago”. The accompanying picture is entitled “Attempted bridge proposal for Yokohama Triennale 1973”, but little of this scanty composition of inkblots and lines evokes connotations to a bridge. The idea of sending a proposal for a work to a triennial that was held on the other side of the globe thirty years ago resembles most of all an absurd, humorous gag. But even a hopeless attempt to create an image as an avant-garde pioneer can have a critical downside. For being ahead of the times is an important component of the idea of the originality of the avant-garde – a concept that, despite all attempts at deconstruction, is still a determining factor when it comes to the artistic and financial value assigned to a work of art, an idea that every so often results

in dubious attempts at backdating.

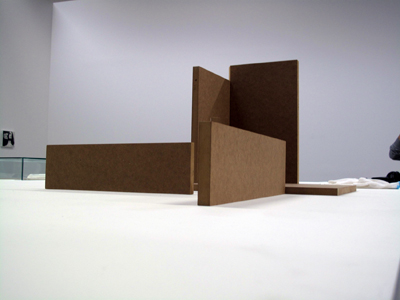

The white cube is again the pivotal point in Museo de Pasatiempo or MPT: a proposal for a board game presented as “the optimum game for people interested in art”. Three years later, Museo de Pasatiempo was actually realised, when Nicolaisen created a number of specimens of the game: six rectangular components made of MDF, along with the rules of the game in six languages, were placed in a paper bag and launched with the slogan “It comes in a bag!” The proportions of the game’s pieces were more or less random, since the artist had picked them out of a bin of cut-offs from a carpenter’s workshop which produced units for museums and galleries. By reading the rules, the player was told to construct an exhibition space with the five largest pieces, while the last piece was to function as a work of art that could be positioned around the room. In other words, Museo de Pasatiempo turned all its players into participants of a pseudo hobby-like art sphere. On one level, this work is reminiscent of Fluxus’ and conceptual art’s instruction pieces, where the viewer became a co-producer of art works. But something made it radically different.

Whereas the instruction pieces of the 1960s tried to break down the hierarchy between the art producer (the artist) and the art consumer (the viewer), so attacking the sublime role of the artist,

Nicolaisen’s game does not transform the viewer into an artist, but rather a curator. One might think that this change of roles was primarily a critique of the new curator role that emerged during the 1990s, when curators became “artist curators”, operating independently of the art institutions and being extremely active in the production of meaning surrounding works. But according to Nicolaisen, Museo de Pasatiempo is equally a criticism of, and an alternative to, today’s empty, white exhibition spaces.

_________________________

press (norwegian):

Med GULT LYS på Samtidsmuseet

Av BJØRN ZARBELL-ENGH SVEN-ERIK RØED (FOTO)

Publisert: 01. oktober 1998, kl. 02:00

Det varme gule lyset fra drammenskunstneren Terje Nicolaisen (34) ønsker publikum velkommen til utstillingen Frie Kunster i Museet for Samtidskunst.

Folk oppdager ikke kunstverket med det samme når de skrider opp den brede marmortrappen i bygningen som tidligere huset Norges Bank. En liten lapp på veggen forteller at det gule lyset er kunstnerens verk, det gule lyset som skaper den lune stemningen i den mektige trappeoppgangen.

- Det er det som er så fint. Kunstverket blir anonymt. Folk opplever verket før de mobiliserer de mentale sperrene «hva er dette for noe tull», sier Terje Nicolaisen.

Han er vant til å overraske og forundre, drammenskunstneren som har gjort det gule lyset til sitt kunstneriske varemerke. Han har vakt oppsikt med lysinstallasjon i den tyske byen Münster og lyst opp Kunstnernes Hus under Høstutstillingen. Litt overrasket ble han selv også da han ble invitert til utstillingen i Museet for Samtidskunst som en av fem unge norske kunstnere.

- Museet for Samtidskunst er en bastion i norsk kunstliv. Det er veldig hyggelig at museet åpner dørene for unge norske samtidskunstnere. Og det er ekstra hyggelig å være en av de fem som inviteres inn.

Terje Nicolaisen gjør som tittelen på den svenske filmen «Jag är nyfiken gul» når han arbeider med sine lys-installasjoner. Han maler lyspærene med oljefarger, kadmium gul på tube, samme farge man bruker til oljemalerier.

- Det blir forskjellig fra gang til gang, forklarer han. Gult er en spennende farge, synes Terje. Gult er pestfargen til sjøs, på sykehuset markerer gult karanteneavdelingen for smittsomme sykdommer. Gule roser betyr svik. Men i Østen er gult hellig og i den kristne religionshistorie er gull glorien, det hellige skinn.

Terje Nicolaisen jobber ikke med det gule lyset til daglig. I arbeidsrommet i Frognerveien jobber han med tegninger, med blekk og vannfarger. Til helgen åpner han en utstilling med tegninger hjemme hos performancekunstneren Liv Reidun Brakstad (Brakstad Inkl. Konsept), hun som vasket stoler på Høstutstillingen. Hun driver Brakstad Konsept inkludert galleri på Grünerløkka, med gjesterom for gjestende kunstnere. Terje Nicolaisen skal stille ut i stuen og gjesterommet.

Så han beveger seg gjerne utenfor kunstens merkede stier, den allsidige og fargerike kunstneren fra Åskollen. Med svennebrev i murerfaget og idéhistorie og engelsk grunnfag ved siden av kunstutdannelse fra Trondheim og Bergen. Musiker er han også i casio-orkesteret Dekadanse. De stiller i smoking og spiller Frank Sinatra og evergreens på et knøttlite Casio-orgel, populært innslag på årets Quartfestival i Kristiansand. Men nå er det først og fremst Frie Kunster på Museet for samtidskunst. I selskap med Hanna Høiness, Lotte Konow Lund, Erik Pisani og Hilde Rognskog. Og utstillingen varer ut november.