Per Teljer

Translation from Swedish: Tom Ellett

At Skara Sommarland (a popular tourist attraction in western Sweden where pale Swedes spend a small fortune on making fools of themselves in public with an orgy of beer, fast food, candy floss, go-karting, bungee jumping, water games of various kinds and so on) in the mid 1990s, the owner Bert Karlsson decided that gypsies were to be denied admission to all these wonderful attractions on the grounds that any individual with the slightest drop of Romany blood was a potential kleptomaniac.

Hi Per, I don’t know if you remember that we discussed gypsy tendencies and the like in relation to my work (you said you could see such a thread). Now I’m going to produce a catalogue for a solo exhibition at Tegnerforbundet, and I was wondering if you fancied writing an article about this, as brief or long as you like … Terje Nicolaisen and the gypsy artist or whatever … What do you think, eh? Like the idea? Terje. E-mail from Terje Nicolaisen, 17 October 2000

“Gypsies” – immediate associations: stout women with moustaches, wrapped up in numerous colourful items of clothing, thin men with thicker moustaches in tailor-made costumes, and owners of big, rusty old Mercedes.

In some respects, Terje Nicolaisen would get along well as one of these men – the jargon is there somewhere, albeit only as part of a wider context, but it is entirely conceivable that Terje would find it great fun to climb out of a big Mercedes, close the door and walk a couple of paces before locking it with a habitual touch of the remote control.

Romany folk seem to possess a higher form of pride, a stronger desire to preserve their dignity than in many other Western cultures (not least in Scandinavia). In the case of the men, this dignity usually manifests itself in the aforementioned costume; “the clothes make the man”, as people used to say. This is also something that Terje’s works have often touched upon, albeit normally indirectly, as an aesthetically concealed statement. It may manifest itself, for example, in a desperate effort to arrive at the discount supermarket as elegantly dressed as for a Nobel Prize ceremony, in order to briefly suppress the knowledge that you don’t have the financial means to shop at quality food stores. The plastic bags in the bottom drawer in the kitchen reveal as much about people’s social standing in Scandinavia as the state of their teeth does in other countries.

In the very first work I saw by Terje Nicolaisen (then a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Trondheim), he seized on just this fact (probably without starting with gypsies). The work consisted of a large number of baskets from the RIMI supermarket, arranged in various more or less sculptural situations, ready-mades from the everyday life of the lower classes. He subsequently developed the idea by combining these baskets into simple skeletal structures that people could grab hold of or wear directly on their body. In a series of photographs, he flaps around with these structures on his body, like a loser Icarus who, through a dark suit and RIMI wings, is striving to elevate and raise himself above his true social situation.

Gypsies have always been regarded in Scandinavia as work-shy conmen, swindlers, in much the same way as vagrants. Their allotted place is a second-rate funfair surrounded by an abundance of coloured lights, illuminations flashing in series, colourful clowns and other glass-fibre junk.

We are drawn to the coloured light as instinctively as moths.

In Terje Nicolaisen’s work “Yellow Light for Otto Plonk”, “Yellow Light at Kunstnernes Hus”, “Yellow Light at the Museum of Contemporary Art” and so on, the similarity to the above image is striking. In this work, Terje focuses more on the core idea that anything can be sold if you can persuade the customer that he or she cannot live without this particular product. The work itself consists, in short, of a number of light tubes, painted with oil paint and placed in one or more rooms. The visual effect is most powerful when seen from outside at night. So what is the meaning of this work? I have no desire in this article to bamboozle myself with notions of “space” and other aesthetic reflections – what is more interesting is how these works come to be exhibited. Here too, the strongest side of Nicolaisen’s artistic personality comes to the fore, the role of the businessman or horse-trader who can make the wheel spin round next to nothing.

Going a step further, we can clearly see a kind of political statement in this: someone or something is exposed, and it is not Nicolaisen or the onlooker, but the very structure of which we are all part. This work is indispensable in this particular situation, only for you my friend! I clearly remember a discussion I had with Terje at a party, at the time when these works were beginning to be set up and exhibited in various places, about what was the true meaning of his work. To begin with, the explanation was pretty comprehensive, incorporating numerous completely acceptable theories.

However, the longer this discussion continued, with arguments bouncing back and forth, the clearer the true intention became – and when Terje finally put an end to any further debate with a big, hearty laugh and a cry of “Cheers!”, everything suddenly became crystal clear. In essence, it is a question of entrenching an idea and an attitude so skilfully that other people will buy it, warts and all. That, damn it, is no easy task, and many people try it without success, while the majority of those who do manage it do not even have the guts to acknowledge it. This is the situation in which Nicolaisen seems to be most at ease, openly flaunting his sales patter coupled with the laid-back style of a dandy. This can often be perceived as kitschy and slightly vulgar, and indeed, why should it not be? It is this side to Nicolaisen’s artistic personality that does most to encourage associations with the superficial aspects of gypsy culture (i.e. the prejudices we have about it): the costumes, big Mercedes, funfairs and so on.

Nicolaisen seems to have an inbuilt need to provoke and confront those around him with his works and his views on the social rules by which we live our daily lives. With great intensity he presents us with his world of ideas, which can easily prove a source of irritation, and on numerous occasions he has certainly been asking for a punch on the nose, but has got away with it thus far (to my knowledge at least). The great kick comes when he succeeds in making us experience a sense of anticlimax when we have seen through the castle in the air and thereby discovered the criticism of our existence or its meaninglessness: Was that it?

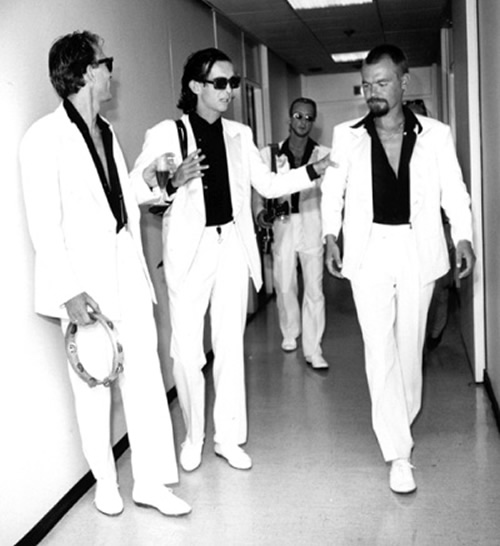

To crown all this, Nicolaisen is a member of the Casio dance band Dekadance, which bases its entire existence on preprogrammed pop tracks. The band was probably formed more for the chance to parade wearing black suits and Ray-Bans, with slicked-back hair, than out of any desire to present high-quality music. Dekadance performs mainly on ferries to Denmark, at weddings, Christmas parties and other public jamborees, which again fits in with the rest of Nicolaisen’s artistic persona and open attitude. When planning this article, I got in touch with a close friend who, I knew, owned a Christmas CD by Dekadance, thinking that this would give me further inspiration. So I got chatting to this friend and asked if he had the disc handy, but he merely shook his head and laughed. “No, damn it, I’ve given that one to the charity shop!”