Ingvild Krogvik (2011)

Published in the book

Supplementary Notes 1994 - 2011 on

Selected Proposals 1995 - 2005

Henie Onstad Art Center, Høvik (2001)

Utopia as a Critical Tool

- Terje Nicolaisens Proposals 1995 – 2005

The number in clams refer to the book in which this essay was published: Supplementary Notes 1994 - 2011 on Selected Proposals 1995 - 2005

Ingvild Krogvig

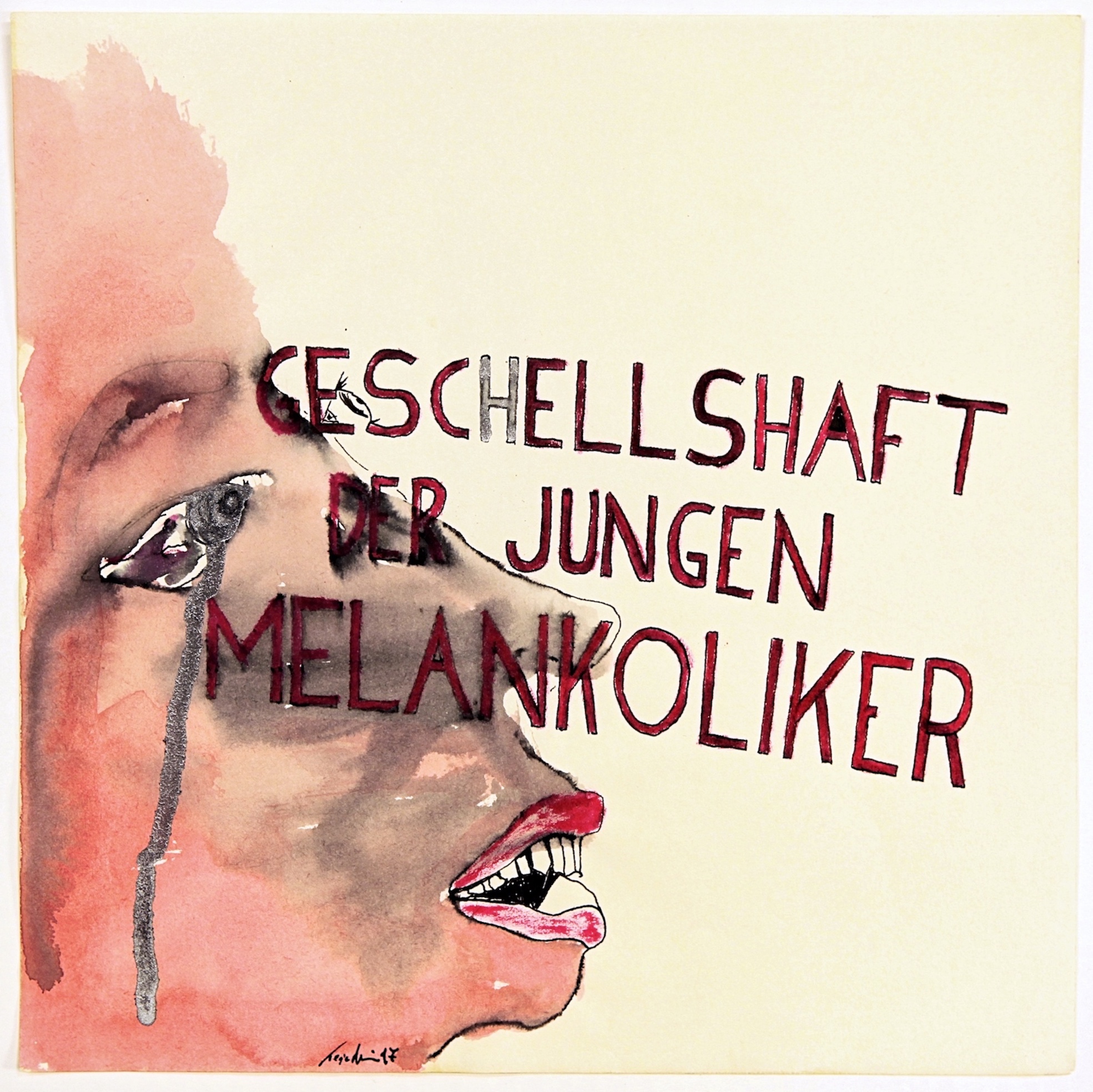

In a drawn situation report from the Bjarne Melgaard exhibition at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in 2010, a female guide in a short, flowing mini-skirt is showing art to a group of children. Terje Nicolaisen’s drawing is entitled Communicating Art (2010). The work of art that the group has gathered around has a typical Melgaard motif: a man is balancing on a gigantic, red penis while another man mounts him from behind. In the caption, the guide is saying to the children: “Bjarne Melgaard’s art contains many figures of apes. If you look around, you will see other animals too. Why is Melgaard so interested in animals? Do you have a favourite animal that means something special to you?”

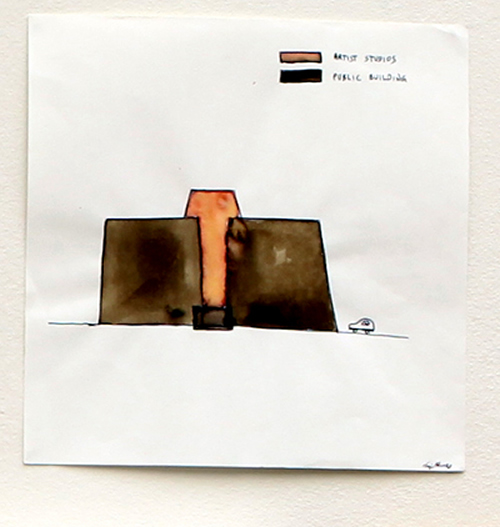

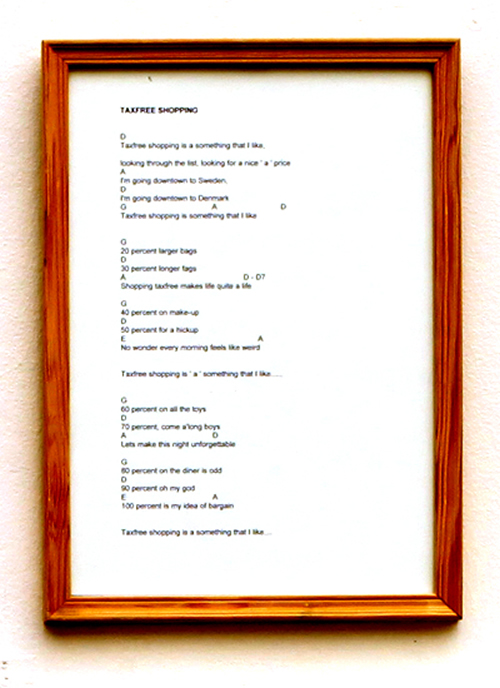

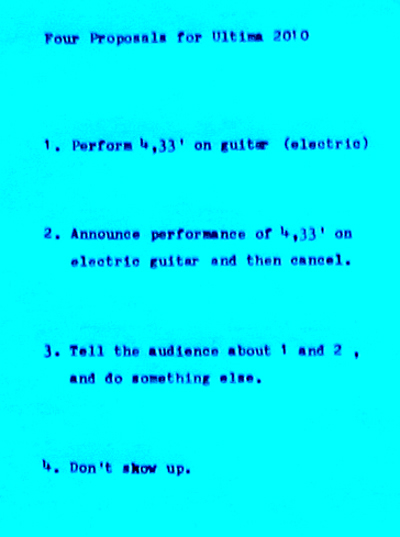

Why this beginning? Perhaps because the drawing reveals Nicolaisen’s ability to capture the absurdities, inconsistencies, taboos and discrepancies in the art world and in life in general. Nicolaisen’s methodology manifests itself in different ways, in media such as performances, paintings, sculptures, texts and drawings. Its clearest manifestation is perhaps to be found in his proposals: suggested works of art, contrivances and staged social situations that Nicolaisen has been working on since the middle of the 1990s. Each of these proposals consists of a short, descriptive text accompanied by a sketch. The texts have a relatively standardised form: they start by pointing out a problem, small or large, which the artist feels the need to get to grips with. Sometimes he philosophises for a short while about the problem, but more often, the text springs straight from the problem and over to a concrete suggestion for solving it. The drawings accompanying the text can almost be regarded as illustrations. Executed in rapid strokes, they effectively communicate the essence of the proposed solution.

Imaginative proposals are an old tradition when it comes to architecture: it should suffice to mention the graphic artist Giovanni Battista Piranesis’ (1720 – 1778) gothic prison fantasies or the architect Étienne-Louis Boullée’s (1728 – 1799) grandiose, neoclassical buildings, or from more recent times,

the British group of architects Archigram’s Walking Cities wandering round on gigantic, hydraulic legs. Proposal-based works have a much shorter history in the field of fine art. Some sporadic examples occurred during the periods of Dadaism and Surrealism, but it was only after the Second World War that the concept of the tentative work of art was studied systematically.

An important figure in this connection was John Cage (1912 –1992), who during the course of the 1950s launched a number of scores, i.e. short, text-based instructions for musical works. About a decade later, the idea that a work of art did not need to be an object began to make its mark in the world of fine art. Fluxus, the artist network that emerged amongst Cage’s students at the New School for Social Research in New York, played a significant role in this development. The members of the group cultivated the event with great zeal and developed notations for actions as a distinct type of work. The Fluxus movement’s concept-based, non-media specific, performative and process-orientated activities were an important prerequisite for the conceptual art that emerged towards the end of the 1960s. [30] [31]

If we are to place Nicolaisen’s proposals within a particular art tradition, it must be the tradition of conceptual art, even though, visually speaking, his works do not have much in common with the best known conceptual art works. His playful, often expressive pencil strokes and the reclining, yet strong irony of his texts seem opposed to the aesthetic puritanism and seriousness of content that are normally associated with conceptual art. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine Nicolaisen’s proposals without conceptual art as a backdrop.

There are two things in particular about the historic movement of conceptual art that pre-empt Nicolaisen’s proposals. One is the movement’s insistence that the most important aspect of a work of art is not its visual idiom, but the idea it communicates. The aim, as Sol Le Witt put it, was “to engage the mind of the viewer rather than his eye or emotions”.1 The traditional, illusionary or purely form-based work of art was replaced by works with fragmented forms, in which the conceptual content was loosely formulated. In this way, the viewer was obliged to adopt an active role as co-author of the work, if some kind of meaning was to be established. The recognition that a work of art functioned first and foremost as a springboard for activities of the mind paved the way for works that consisted precisely of proposals, drafts and plans.

Another important foundation for the emergence of the proposal as a genre was the critique of sculpture as monument, but forward by the conceptual artists. In the climate of the 1960s’ scepticism of authorities, heroic monuments of political leaders and artists were seen as irrelevant, almost hilarious. Conceptual art introduced a new notion of sculpture which was in many ways the antithesis of traditional sculpture’s function as monuments and memorials. Marble, stone and bronze were replaced by less permanent, more prosaic materials such as gravel and earth, water and wax, felt, asbestos and asphalt. These materials were processed by means of simple methods that were a far cry from those traditionally thought of as sculptural techniques. The proposal genre seemed well suited to contributing towards the trend of creating art that criticised the traditional monument, not least because it gave artists the opportunity to work satirical through the use of exaggerations and absurdities.2

Some of the proposal works produced during the early stages of conceptual art had much in common with Fluxus’ instruction works; they were directed at a perceived recipient who could realise the work by means of simple techniques. One typical example is Lawrence Weiner’s (1942 – ) Statements. Other works were more difficult to realise and seemed to address a larger, yet at the same time less tangible, public. The fact that many of the proposals in the latter group were utopian in character by no means weakened their critical potential. A good example of this is Joseph Beuys’ proposal from 1964, where he suggested increasing the height of the Berlin Wall by 5 cm for purely aesthetic reasons.3 The newly erected wall – Germany’s great trauma – was thereby reduced to an aesthetic object and appraised in terms of the aesthetic norms of late Modernism. The result was a collision

between an artistic and a political discourse, in which both were the objects of criticism.

However, Nicolaisen’s curiosity about the proposal genre was not triggered by Weiner or Beuys, but by two discoveries: the first was the catalogue for Sculpture. Projects in Münster 1987, which he came across by chance at the end of the 80s. The exhibition, which Nicolaisen never witnessed himself, consisted of sculptural works erected in public places in Münster. But he studied the catalogue in detail. Produced in good time prior to the exhibition, the catalogue contained texts, illustrations in the form of photographs and working drawings of planned projects. Several of the catalogued projects were illustrated by means of photographic montages and it was in some cases impossible to determine whether the work had actually been produced or not. This uncertainty made Nicolaisen realise that it did not really matter one way or the other. The works in the catalogue had just as strong an effect, whether they had been realised or not.4

The other discovery that led Nicolaisen to the proposal genre was Claes Oldenburg’s (1929 – ) proposals for monuments. These works were begun in the middle of the 1960s and consisted of drawings of enormous, imaginary monuments inspired by trivial, everyday objects such as fried eggs, vacuum cleaners, ice lollies and clothes pegs. Oldenburg’s monumentalisation of an everyday world of objects can on one level be interpreted as the logical continuation of his normal size pop art sculptures. But according to the American art historian Barbara Rose (1938 – ), these drafts of monuments were not just conceived as a satirical comment on “the banality of American life”, but also an expressionof the heroic monument’s irrelevance in modern society.5

Oldenburg’s monument proposals commented not only on American life, but also in one instance on Norwegian life. Frozen Ejaculation (Ski Jump) from 1966 was a draft for a colossal sculpture of a frozen ejaculation that was probably meant to complement Gustav Vigeland’s phallic Monolith. Oldenburg linked the eroticism in Vigeland’s work to Oslo’s image as a city of winter sports, emphasised by the drops from the gigantic ejaculation ending in a frozen pond on which the public could enjoy themselves skating.6 The work by Oldenburg that made the strongest impression on Nicolaisen was of a rather different kind; this was a small, bronze model of a topographical map with an enormous door handle that stretched from Skeppsholmen (the location of Moderna Museet) and in towards Stockholm city centre. The work, entitled Door Handle and Locks, and other Oldenburg

proposals, was a confirmation of the genre’s potential to exceed boundaries. He realized that working with proposals opened up an opportunity for breaking new ground.7

The artist as a town planner

Even though Oldenburg’s monument proposals were important to Nicolaisen, his own proposals were based on something different. When Oldenburg launched his proposals in the middle of the 1960s, they were clearly critical of what the American critic and theorist Rosalind Krauss (1941 – ) called “the logic of the monument”:8 Meaning the idea that “the sculpture is a representation […] standing on a particular site and telling in a symbolic language a story about this site’s meaning or use.”9 But even though Oldenburg’s works broke away from the function of memorial, his proposals still had a symbolic function. As time passed, and several of them have been erected, it has become clear that these works have not managed to free themselves from the monument’s status as a decorative and impressive object. [32] [33]

Few aspects of Nicolaisen’s proposals are reminiscent of the logic of the monument. Most of his suggestions are about improving existing structures, making new devices or staging social situations – not about launching sculptural objects. A willingness to make improvements also characterize the proposals Nicolaisen has made for the city of Oslo. Ibsen Tunnel Improvement [pp 115 / 174, 175 / 189] is a typical example of this. The textual part f the work makes it clear that the aim has been to give the Ibsen Tunnel a real facelift: “An easy and tasteful intervention would be to install […] slightly enlarged light bulbs around the openings […] referring to the makeuplights around the mirror at the backstage of the theatre.”10 Not only does the project seek to lend the absurd combination of Ibsen and a tunnel some sort of logic, but it also gives driving in a tunnel a touch of glamour:

The sensation of driving into this heavy lighted

hole – going in high speed into the limelight

of fame – would increase both the visual

and the physical experience of driving downtown.

Not to mention the mental notion of

stardust.12

The idea that a dirty tunnel can be transformed into a kind of Moulin Rouge for traffic at first appears humorous and absurd. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating idea and immediately one turns to the drawing in order to study the practical design of the project. The visual scenario that Nicolaisen has drawn is, however, more surreal than the accompanying text. It shows the back of a woman sitting in front of a large make-up mirror in a theatre dressing-room and, seemingly oblivious of the surrounding two large highways that disappear into the lit tunnel opening of the neighbouring mirrors, she is putting up her hair. For the most part though, the sketches accompanying Nicolaisen’s proposals are relatively realistic illustrations.

Several of the suggestions for urban improvements are characterised by a downto-earth, even practical attitude, such as Oslo Circle Line [pp 106 / 168, 169 / 188], a proposal to build a new, circular underground line in the city. This idea was launched before that of the existing circular line and is a far more ambitious: Nicolaisen’s project only has stops at places formerly not served by the underground, such as Solli Plass, Aker Brygge, Hovedøya, Bjørvika, Loenga and Grønlandshagen. All stops are chosen according to his own preferences and movements, with good reason: “Since I cannot spend all my time on city planning, the stops suggested are of subjective choice.”13 In spite of this subjective element, the artist has here adopted the role of bureaucrat and politician. At the same time, his position is one lacking in formal power, so his statement will almost certainly be ignored. In this context, the work will perhaps primarily be an image of the powerlessness inherent in the distance between thoughts and actions that prevails in our modern information society – a society in which most of us brazenly put forward solutions to everything from the conflicts in the Middle East to public transport problems, knowing that we have neither the authority nor the incentive to transform our suggestions into political action.

In what way should we interpret Nicolaisen’s local political proposals as art? What distinguishes them from the proposals that are put forward in political and bureaucratic fora? One of the most important trends after the Second World War has been that more and more of our everyday lives have been incorporated into the sphere of art. As the conceptual artist and theorist Andrea Frazer put it: “to reach everyday people and work in the real world, we expand our frame and bring more of the world into it.”14 But however far this trend goes, the rules governing politics and aesthetics respectively will never quite concur. One significant difference is that the artist, in contrast to the politician, has potentially more freedom, not least when it comes to the proposal as a genre. As Nicolaisen himself emphasises: “many practical, economical and ethical reflections that could lead to obstruction are not present in these artworks.”23 And it is perhaps precisely here that the strength of Nicolaisen’s proposals for Oslo can be located: they rise above practical objections and demonstrate that the scope of ideas for the city as well as who should submit them perhaps ought to be widened.

Other city proposals by Nicolaisen are a far cry from the sphere of politics. They are poetic and sometimes utopian in character. Sliding Door [pp 116 / 189] belongs to this category. This is a proposal to construct an electrically driven sliding door which is then slotted into a tramline and sent off on an aimless ride through the town. A similar concept is to be found in Tram II, which was conceived as a project for Oslo Open [not in the exhibition]. The idea was to strip down a tram until only the chassis and engine remained and allow it to drive around the city like a silent, iron skeleton. These works are reminiscent of the historic avant-garde’s desire to turn life into art and to transform everyday life “by means of the poetic”.24 If Sliding Door and Tram II had been realised, the most striking effect would perhaps have been a form of defamiliarisation. Defamiliarisation means turning something familiar, and hence automatically perceived, into something strange. According to the Russian literary theorist Victor Sjklovskij (1893 – 1984), who launched the idea of defamiliarisation as an artistic technique, it was a matter of taking words out of their usual context and putting them into new ones, so that our habitual use of language was disturbed. In Sliding Door and Tram II, not only the artistic language, but also reality can be perceived in a new way.26 A sliding door or a stripped tram on a lonely journey through the town would be an eye-opener as we make our habitual way through the city.

The artist and the art institution

None of Nicolaisen’s Oslo projects have been realised in practice. However, some of them have been realised within the confines of art institutions – usually on invitation, but sometimes also without invitation. Parallelle Projekte in der Stadt Münster is an example of the latter. The catalogue from the exhibition at Münster in 1987 had played an important role in Nicolaisen’s formative years and when the exhibition was again to be held ten years later, in 1997, Nicolaisen decided to participate with a parasitic project.30 He went to Münster, found an appropriate exhibition space in a pavilion, produced a catalogue, posters, postcards and a press release and attended the official press conference. In short, he acted as if he were part [34] [35] of the Sculpture Project Münster. His actions were fuelled by impatience, a feeling of not wanting to wait until he was seventy. 31

But Nicolaisen’s intervention also had a more principle aspect to it; it could be seen as a criticism of the regulatory role of the art institution – a role stemming not only from ideas of “quality” and “topicality”, but also from the intention to “reward”. This idea lies behind retrospective exhibitions, but it is also present at biennials like that in Münster where “deserving” artists are invited to exhibit their works after long carriers as artists.

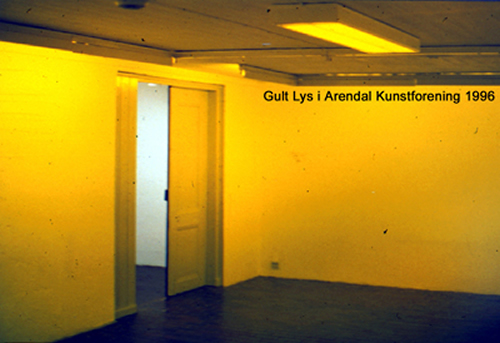

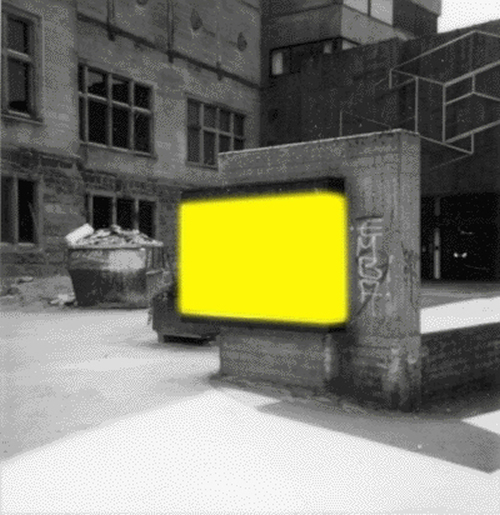

The work that Nicolaisen presented at Münster was part of a larger project entitled Yellow Light, which had been shown at a number of venues.32 It was the first of a long series of works by Nicolaisen that comments on the art institution. The project involved emptying the gallery space of art objects and replacing them with an intense, yellow light. Nicolaisen’s use of gallery space had predecessors in conceptual art from the end of the 1960s to the middle of the ‘70s. During this period, artists such as Mel Bochner, Marcel Broodthaers, Peter Weibel, Hans Haacke and Michael Asher began criticising the institutional contexts art operated in. This marked the beginning of the practices that were later to be called institutional critique. Many of these early works aimed to show how the white cube, with its white walls, artificial lighting and shuttered windows, contributed to separate art from the real world. The idea was that the white cube upheld Modernism’s dogma about the autonomy of the work of art.

Yellow Light was produced three decades later, at a time when the Modernist discourse on art’s autonomy discourse was more or less irrelevant. But the point of departure for the series was nevertheless an “anti-white-cube attitude”. Nicolaisen later explained the motivation behind the project:

It seemed to me […] that whatever you put into

a white cube would function as art. This led to

the assumption that the white cube itself is

the genuine art constitution and that the space

is the object and the art it’s hostage.33

In Yellow Light, the gallery itself was turned into a readymade, as Weibel, Asher and others had done in the early days of institutional critique. But whereas Weibel and Asher emptied the space in order to show the gallery as an architectural framing device, Nicolaisen chose a different strategy to objectivise the space. The gallery itself was closed to the public during the exhibition and could only be seen from outside. In this way, the gallery was transformed from a venue for socialising and experiencing art to an inaccessible sphere that only emitted an enigmatic, yellow light.

For those unfamiliar with Nicolaisen’s projects, the work appeared merely as a yellow light shining from a room. One of the core ideas of Nicolaisen’s oeuvre has been precisely that of creating a non-artistic room around his own works. The works are often “unrecognisable as art” and appear to be, for example, urban spaces or sites.34 Nicolaisen’s intent was to capture the attention of the viewer “without him having to navigate through an understanding of art […] Freed from this particularly problematic and mystical understanding, the beholder has related to the art work on a 1:1 basis, through an open and average degree of interest. In this context, art has been revived, albeit without identity.”35

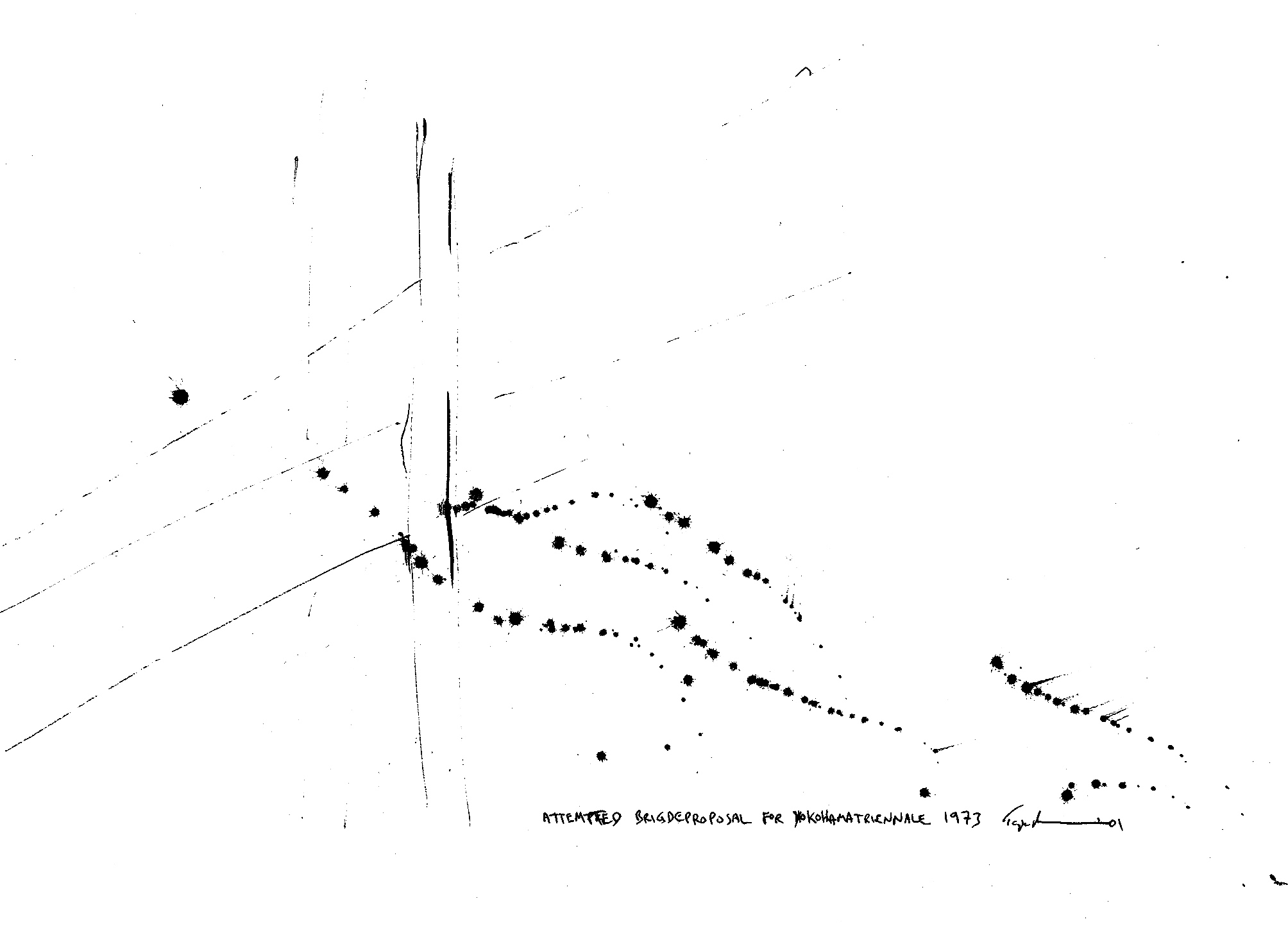

Another example of Nicolaisen’s ability to project himself in contexts he is not a part of is Yokohama Trienniale 1973 [pp 112n/ 188]. This proposal is simple enough: “To send a proposal to a triennial that already took place years ago”.36 The accompanying picture is entitled “Attempted bridge roposal for Yokohama Trienniale 1973”, but little of this scanty composition of inkblots and lines evokes connotations to a bridge. The idea of sending a proposal for a work to a triennial that was held on the other side of the globe thirty years ago resembles most of all an absurd, humorous gag.39 But even a hopeless attempt to create an image as an avant-garde pioneer can have a critical downside. For being ahead of the times is an important component of the idea of the originality of the avant-garde – a concept that, despite all attempts at deconstruction, is still a determining factor when it comes to the artistic and financial value assigned to a work of art, an idea that every so often results

in dubious attempts at backdating.

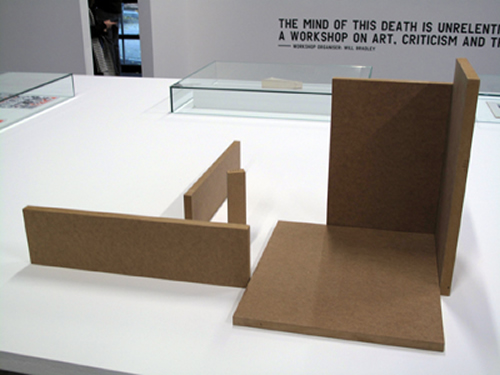

The white cube is again the pivotal point in Museo de Pasatiempo or MPT [pp 54, 84 / 158 / 179]: a proposal for a board game presented as “the optimum game for people interested in art”. Three years later, Museo de Pasatiempo was actually realised, when Nicolaisen created a number of specimens of the game: six rectangular components made of MDF, along with the rules of the game in six languages, were placed in a paper bag and launched with the slogan “It comes in a bag!” The proportions of the game’s pieces were more or less random, since the artist had picked them out of a bin of cut-offs from a carpenter’s workshop which produced units for museums and galleries. By reading the rules, the player was told to construct an exhibition space with the five largest pieces, while the last piece was to function as a work of art that could be positioned around the room. In other words, Museo de Pasatiempo turned all its players into participants of a pseudo hobby-like art sphere. On one level, this work is reminiscent of Fluxus’ and conceptual art’s instruction pieces, where the viewer became a co-producer of art works. But something made it radically different. Whereas the instruction pieces of the 1960s tried to break down the hierarchy between the art producer (the artist) and the art consumer (the viewer), so attacking the sublime role of the artist,

Nicolaisen’s game does not transform the viewer into an artist, but rather a curator. One might think that this change of roles was primarily a critique of the new curator role that emerged during the 1990s,when curators became “artist curators”, operating independently of the art institutions and being extremely active in the production of meaning surrounding works. But according to Nicolaisen, Museo de Pasatiempo is equally a criticism of, and an alternative to, today’s empty, white exhibition spaces.25

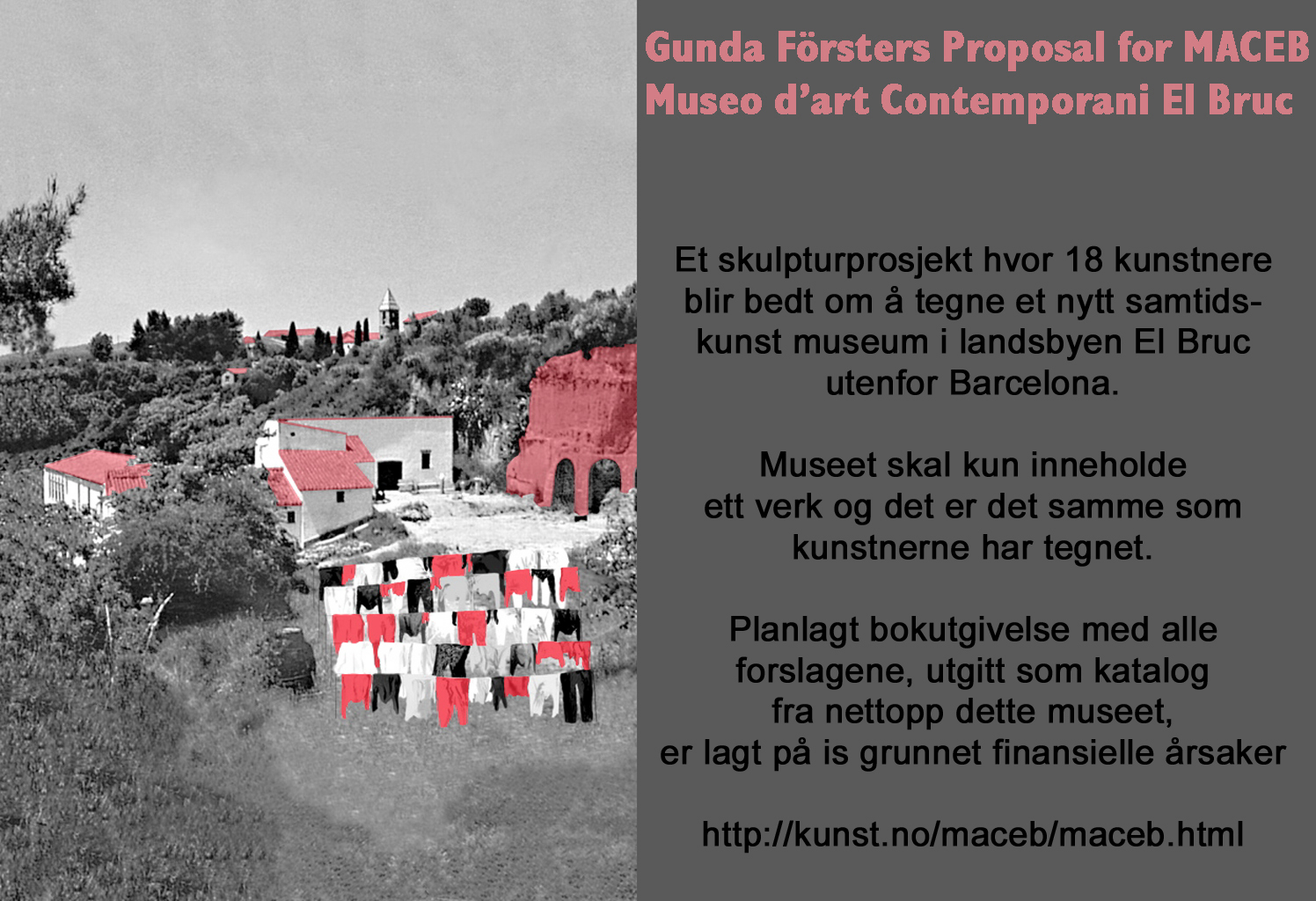

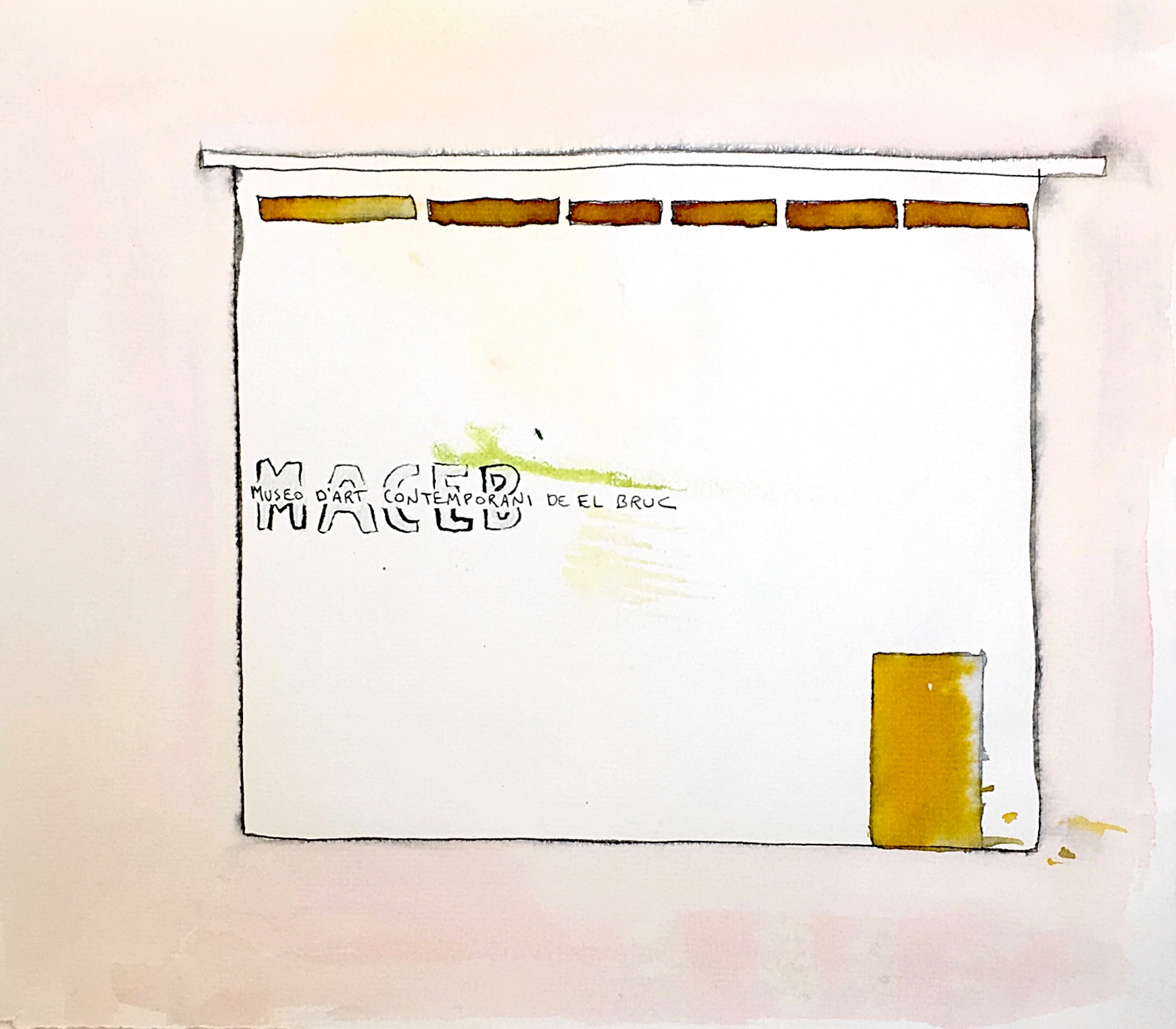

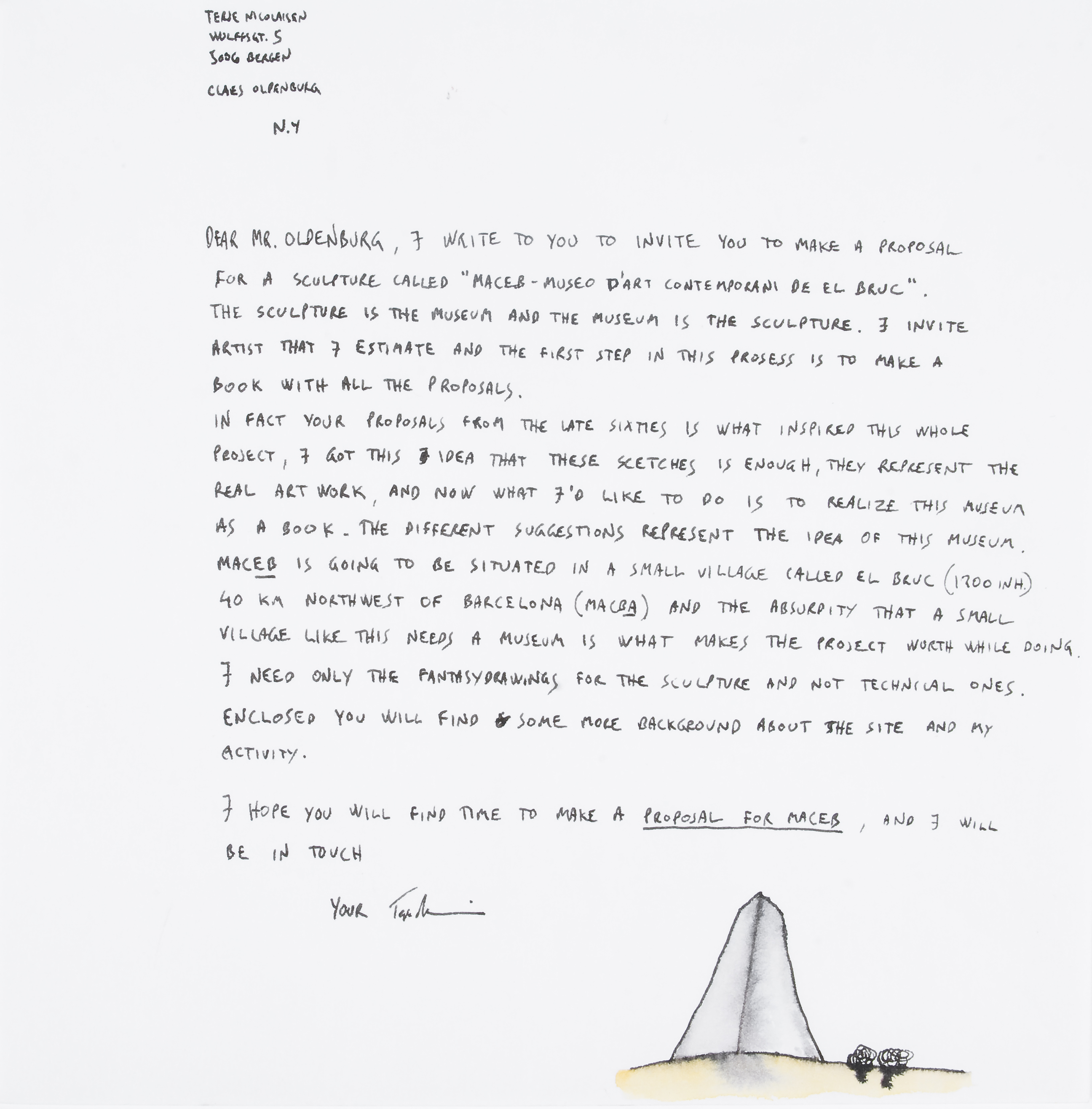

However, Nicolaisen’s criticism of the art institution extends far beyond an attack on the white cube. In MACEB – Museo d’artContemporani de El Bruc [pp 43, 63, 103 / 121 – 123 / 177, 181, 187], Nicolaisen subjects the more recent trends in the museum world to critical analysis. This work is a proposal for a museum of contemporary art in the village of El Bruc outside Barcelona. In contrast to today’s enormous museums, this is a building of a few square meters, scaled-down to suit the site: “The museum´s [36] [37] size is according to the number of inhabitants (approximately 800) in this village. Therefore, the museum will consist only of one art work, namely the museum itself.”26

Despite its exaggeration, MACEB sums up one of the most prominent tendencies in today’s museum policy: that the building itself now seems to be the museum’s most precious exhibition object. This phenomenon really became clear when the Guggenheim Museum opened in Bilbao in 1997 and a large number of visitors stated that they came first and foremost to see the building, and not the exhibitions. Since then, this trend has intensified. When Rome opened its new museum of contemporary art, Maxxi, in 2009, not a single piece of art was in place, which prompted one critic to pose the question “whether art was necessary at all”.27 The proposal to create a museum for contemporary art in a village with a population of 800 may seem absurd, but is in many ways the logical conclusion to the ideas that have legitimised the explosive proliferation of museums and biennials, founded on a belief in the modern museum’s omnipotent significance for urban development. In other words, the idea that dying industrial towns can be transformed into flourishing cultural towns, slums can be turned into attractive residential areas, and completely characterless places can become tourist magnets if museum landmarks are built there.

In another work Nicolaisen investigates the link between the originality of the work of art and its market value. In Recollecting Works – The Lookalike Show, [pp 89 / 186] Nicolaisen suggests collecting all (!) works of art owned by private collectors and public collections in an exhibition called Collected Works. Furthermore, the artists represented are to make copies of their works from memory, and these copies will be exhibited in another section of the museum. Nicolaisen’s proposal is accompanied by a rudimentary sketch in which two sets of pictures hang closely together in an identical configuration. The only difference is that the pictures on the left are drawn with paler and more blurred strokes, indicating perhaps that these are copies. The purpose of The Lookalike Show is probably not primarily to test the artists’ ability to reproduce their own works from memory, but to comment on the myth that has grown up around the “original work of art” – a myth that has been both cultivated and deconstruct throughout large parts of the 20th century. As early as the end of the 1930s, Walter Benjamin foresaw that the concept of the work of art’s authenticity would become meaningless when faced by new reproduction methods such as photography and film.28 And with the advent of Postmodernism, the ideas of “originality” and “origin” were exposed to a farreaching

deconstruction.

Nicolaisen’s Lookalike Show addresses the problem of originality from another angle: it asks the artists to create remakes of their own works. It is not unusual for artists to make new versions of earlier works. Some of best-known examples in Norwegian art are probably Munch’s many versions of his own pictures – versions that are sometimes so alike that the term “copy” would be the best way to describe them. However, Nicolaisen’s Lookalike Show brings something completely new to this practice in that it removes it from the closed sphere of the artist’s studio. If Nicolaisen’s exhibition project had been realised, collectors and those who manage collections would have been faced with a major dilemma: loaning works to Nicolaisen’s Lookalike Show would mean accepting that the work they owned would be copied. In other words, the project would not just have been an investigation into the processes of value change that occurs when works of art are duplicated. It would also have functioned as a sociological study of how the concepts of “copy” and “original” control patterns of behaviour in the field of art.

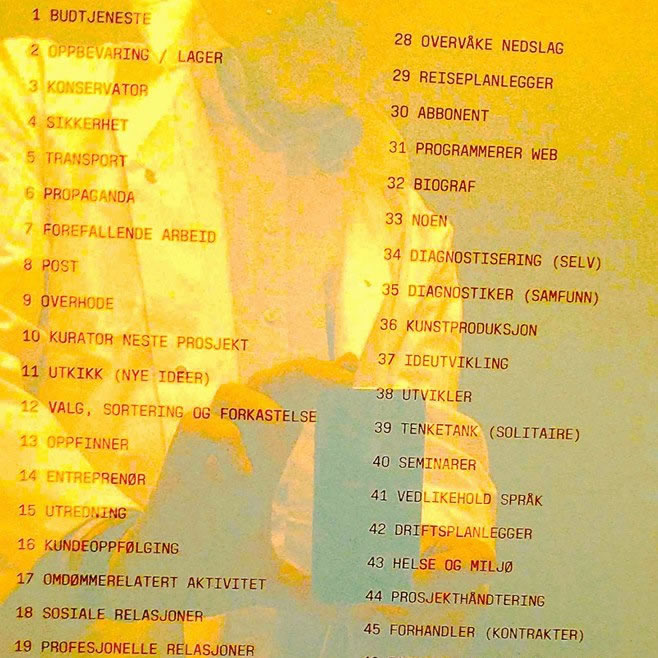

The working conditions of the artist

As we have seen, many of Nicolaisen’s works are targeted at what we normally think of as art institutions, i.e. museums, galleries and biennials. At the end of the 1960s, a new use of the term “art institution” emerged that not only embraced the museum and the gallery, but also the whole social sphere surrounding art.29 In the years that followed, two kinds of institutional critique arose: one was based on an understanding of the art institution as a venue and criticised the activities of the galleries and museums. The other focused on art as a social field. As a result, everything from education establishments of art and art history to distribution channels, critics, interpreters, ollectors, the public and artists became objects of institutional critique.

Nicolaisen’s works are directed at both the art institution as a venue and as a social sphere. A recurrent theme of his works has been the role of the artist, focusing on everything from economic to practical parameters, to the challenges, anxiety and doubt that are part and parcel of the artist’s role. One such work is Artdisposalchambertn [72 / 154 / 183], a proposal for specially designed refuse containers for art. According to the drawing, this consists of a closed container with a rounded top. A narrow slot seems to be designed for discarding stretched canvases and paper works, while a large oval-shaped hole is for throwing away sculptures, video cassettes and the remains of installations. It is easy to be convinced of the need for this practical container when one reads Nicolaisen’s arguments:

As the art world seems to have a well-developed system for exclusion and most artists have not shown nor sold production at stock, the necessity for a recycling system seemed to be appropriate. Not only would an art-disposal possibility relieve the artists from the overload neurosis that unexposed artwork generates, the art world and the world as such would be cleansed of untransported intentions that are known to create aggression.30

The text also explains why art cannot be disposed of at normal recycling plants, but must be treated as a particular type of special waste. If we agree that artwork has an aura, the stocking together of different artworks from different artists would create an uncontrollable auratic radiation, a potentially dangerous situation. A chaotic flow of various intentions and expressions could lead to unintentional effects.31

Aura, the term Walter Benjamin used to describe the authenticity [38] [39] and uniqueness of the artwork, is transformed in Nicolaisen’s ironic universe into a physical phenomenon that, under certain conditions, can pose a considerable radiation hazard. This ironic approach to the concept of the artwork as something unique and authentic is only one of several critical aspects of Artdisposalchambertn. The most important of these is perhaps the uncomfortable point they raise – that for most artists, there exists no large market for the art they produce. Nicolaisen opts to address this reality, of which he is also a part, in an apparently practical and solution-oriented way. The humour her arises in the contrast between the normative and the incorrect. Lack of sales and interest is not usually something artists address, either artistically, or in other ways. Nicolaisen nevertheless throws himself headlong into the taboo and dedicates the work to “all bad artists”.

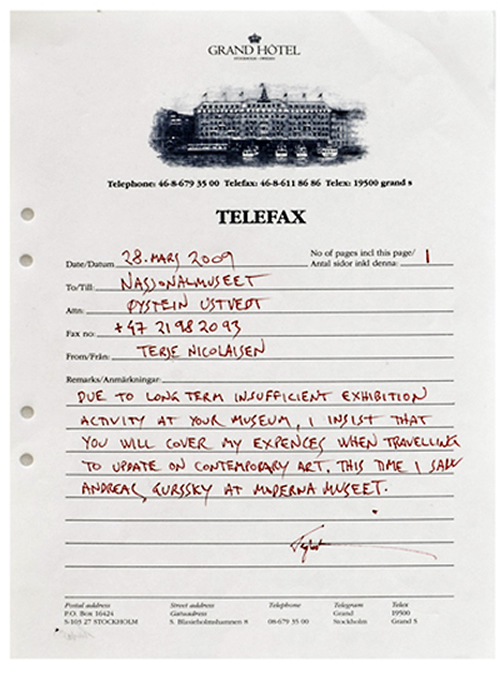

Others of his works focus on the artist as a network player. Here, Nicolaisen approaches the art institution as a particular type of network, whose participants are bound together via social and economic relations. These network structures come perhaps most clearly to light in a work called Norsk Sokkel Award [pp 86 / 160 / 185]. The title indicates that it is “a large work commenting on oil and welfare”, but the work actually has no links at all to the Norwegian oil industry.32 The textual part of the work begins with the following observation: “In the art world, artists very seldom give one another public recognition, except when someone dies or gets really sick.”33 Nicolaisen countered this lack of generosity by establishing a prize, Norsk Sokkel Award, which he awards each year. The award ceremony often takes the form of an intervention. The proposal text states: “At a public event, prepare with a microphone and flashlights. At a specific time during the event, grab the microphone and call people´s attention.”34 The prize itself consists of a 30 – 40 cm long cut-off from an iron beam which has been brushed and polished. But since the winner is only allowed to keep it for a few minutes or hours before Nicolaisen takes it back, the prize is primarily symbolic in character.

The first prize winner was Galleri By the Way in Bergen, which was awarded the prize in 2001, the year after Nicolaisen had exhibited there. The next in line was Klaus Jung, who had been Nicolaisen’s tutor at the Art Academy in Trondheim during the 1990s. The last prize winner was the artist Marianne Heier, who for several years has shown an interest in Nicolaisen’s works. In other words, the prize has been awarded to the artist’s close friends and supporters. Nicolaisen comments on the selection process as follows: “Obviously, the award’s real value decreases, the closer and more openly corrupted this connection is. At the same time, the artistic strength of the project increase proportionally with the violation.” 35

Due to its lack of “secure jobs” and tangible criteria for quality, the field of art is generally regarded as one of the social spheres where nepotism is most widespread. The use of one’s own network to acquire jobs, commissions, services, influence etc is in many ways absolutely necessary in order to pursue a career as an artist, curator, art critic etc. At the same time, this culture of rendering services to friends breaks with the fundamental principle of the Norwegian meritocracy: that what you know, and not who you know, should be the key to your career. Because of this, favours to friends are taboo, a phenomenon that is rarely spoken about and that is definitely not bandied about. Norsk Sokkel Award violates this tacit practice. By rendering the inherent benefit to the artist as the most important, and indeed the only, criterion for winning the prize, we are confronted with a straightforward, undisguised form of corruption that is disarming, yet far from being free of jarring undertones.

Several of Nicolaisen’s works criticising the art institution spring from his own situation as an artist. But the personal and private element rarely invades the work itself.36 The Visa Paintings [pp 57 / 144 / 180] are typical of this. The whole project derives from the fear of not earning enough money.37 For Nicolaisen, the counterpart of this fear lay in the dream of the perfect commission, economically speaking – a dream that resulted in a proposal to create a picture for each of the 872 rooms at the Oslo Plaza Hotel. The proposal text is written in a relaxed tone that in no way divulge the existential angst behind it.

Some years later, Nicolaisen realised part of the idea, but the actual Visa Paintings do not bear witness to any existential anguish either. The codes belonging to expressive painting, which traditionally have been read as spontaneous articulations of the artist’s thoughts and feelings, are totally absent. The Visa pictures are, on the contrary, mechanical paintings, where the format, composition and production method are standardised. Liquefied acrylic paint from a bottle has been squeezed out onto the shortest side of a metre-long piece of paper. The paint has then been spread over the paper in one fast stroke, in compliance with the instructions in the textual part of the work: “They should be made with the speed of visa-cards”.38

With the advent of concept art, there emerged a belief that the new, dematerialised and site-specific practices would undermine art as a commodity. Two of the main supporters of this belief were the critics and theorists Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, who wrote: “since dealers cannot sell art-as-idea, economic materialism is denied, along with physical materialism.”39 However, it rapidly became apparent that snapshots of piles of earth, photocopies, lists of numbers and the other work forms that concept art introduced, could easily be converted into commodities for sale. Nicolaisen’s Visa Paintings were produced nearly three decades after the belief in the conceptual work, merely through its form, could function as a criticism of capitalism, had been undermined. The serious and ideology-burdened critique of the exchange value between art and capital present in early conceptual art is in the Visa Paintings replaced by a completely different mentality. Produced in a way that mimics the act of a Visa-card payment, they could almost appear a tribute to the market forces themselves. But only “almost”, because as is so often the case in Nicolaisen’s art, the whole project ends in a parody – a double-edged parody that not only targets the art collector with his platinum card sticking out of his jacket pocket, but also the poor artist’s utopian dream of a new economic logic where the production and sale of art is as rapid and easy as a direct debit transaction.40

[1] Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on conceptual [40]

art”, in Conceptual art: A critical

anthology, edited by Alexander Alberro/

Blake Stimson, (London: The MIT Press,

1999), p 15. [2] The first Norwegian

work of this genre was Viggo Andersen’s

Vigelandsanlegg from 1976: a proposal to

tear down all the sculptures in the

Vigeland Park and replace them with a

labyrinth-like structure. See Ingvild

Krogvig “Viggo Andersens Vigelandsanlegg:

Historien om et glemt antimonument”, in

Audiatur: Katalog for nypoesi, edited by

Paal Bjelke Andersen, Audun Lindholm and

Thomas Lundbo (Oslo: Audiatur, Gasspedal

and Forlaget Attåt, 2009), p 189. [3]

http://www.walkerart.org/

archive/9/9C4301AEBEAC42EE6167.htm.

Downloaded on 8.12.2010. [4] Interview

with Terje Nicolaisen, Oslo 26.11.2010.

[5] Barbara Rose, Claes Oldenburg (New

York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1979), p

103. [6] Paul Carroll, “The poetry of

Scale” at www.publicaddress.us/downloads/

oldenburg. Downloaded on 27.7.2009.

[7] Other important sources of inspiration

for Nicolaisen are Michael Asher’s texts

and illustrations of planned works, and

Roman Signer’s Nicht ausgeführte Projecte

für öffentlichen Raum (Unrealised

projects for public spaces). [8] Krauss,

though, relates “the logic of the

monument” to the period from the

Renaissance up until the end of the 19th

century. At this point, the first signs

that the logic of the monument was about

to disintegrate became apparent, and with

the onset of Modernism, the “negative

state of the monument” made its entrance,

according to Krauss. The monument now

became abstract in form and “siteless and

to a large degree self-referential”. But

the fact that the 20th century has been

full of referential memorials gives

reason to regard “the logic of the

monument” as a great deal more tenacious

than Krauss seems to do. See “Skulpturen

i det utvidete felt” in Avantgardens

originalitet og andre modernistiske

myter, translated by Agnete Øye (Oslo:

Pax Forlag, 2002), pp 43, 46 and 47.

[9] Ibid, p 46. [10] Terje Nicolaisen,

Selected Proposals 1995 – 2005 (Oslo:

Norsk Sokkel forlag, 2002), p 44. [11]

Ibid. p 44. [12] Nicolaisen, Selected

Proposals, p 32. [13] Andrea Frazer,

“From the Critique of Institutions to an

Institution of Critique”, 1995 – 2005, in

Institutional Critique and After, edited

by John C. Welchman (Zurich: JRP/Ringier,

2006), p 131. [14] Nicolaisen, Selected

Proposals, p 5. [15] Gail Day, “Art,

love and social emancipation: on the

concept ‘avant-garde’ and the interwar

avant-gardes”, 1995 – 2005, in Art of the

Avant-gardes, edited by Steve Edwards and

Paul Wood (London: Yale University Press,

2004), p 322. [16] Viktor Sjklovskij,

“Kunsten som grep”, in Moderne

litteraturteori, edited by Atle Kittang &

others (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget,

1998), p 16. [17] Interview with Terje

Nicolaisen, Oslo 26.11.2010.

[18] Interview with Terje Nicolaisen,

Oslo 26.11.2010. [19] Yellow Light is

not included in the exhibition at the

Henie Onstad Art Centre, but since it has

links to Rjukan 2005, Untitled (1000

meters) and Proposal for Onomáte-Sando,

which are being shown, it is worth

dwelling on. [20] Nicolaisen, Selected

Proposals, p 6. [21] Terje Nicolaisen,

“Kortprosa”, 1995 – 2005, in the

catalogue Terje Nicolaisen (Oslo: Norsk

Sokkel Forlag, 2001), p 14. [22] Ibid.

[23] Nicolaisen, Selected Proposals, p

100. [24] Deliberate bad timing occurs

in several of Nicolaisen’s works, such as

the T-shirts with a portrait of Sune

Nordgren, which Nicolaisen created as an

expression of support for the sharply

criticised director of Norway’s National

Museum of Art, but which were not

launched until several years after

Nordgren had left his post as director.

[25] Yet another episode in the story of

Museo de Pasatiempo occurred in the

autumn of 2010, when its components were

enlarged by 1600% and turned into

Kunsthall Oslo’s permanent exhibition

architecture. [26] Nicolaisen, Selected

Proposals, p 54. [27] Victor Plahte

Tschudi, “Zaha Hadid: Museo nazionale

delle arti del XXI secolo (Maxxi)”, 1995

– 2005, in Morgenbladet, 26.02.2010. The

critic was Marco Lodoli, writing in La

Repubblica. [28] Walter Benjamin,

Kunstverket i reproduksjonsalderen,

translated by Torodd Karlsten (Oslo:

Gyldendal, 1991). [29] Andrea Fraser,

“From the Critique of Institutions to an

Institution of Critique”, p 128. [30]

Nicolaisen, Selected Proposals, p 20.

[31] Ibid. [32] Geir Tore Holm,

“Saksopplysninger/Malerier”, 1995 – 2005,

in the catalogue Terje Nicolaisen, p 11.

[33] Nicolaisen, Selected Proposals, p

72. [34] Ibid. [35] Interview with

Terje Nicolaisen, Oslo 26.11.2010. [36]

One major exception is Norsk Sokkel Award

and the so-called Office works, 1995 –

2005, i.e. letters which Nicolaisen sends

to people he has signed contracts with or

collaborated with. Here, the personal

element is often a core feature of the

work. [37] Interview with Terje

Nicolaisen, Oslo 26.11.2010. [38]

Nicolaisen, Selected Proposals, p 14.

[39] Lucy Lippard and John Chandler, “The

Dematerialization of Art”, 1995 – 2005,

in Art International 12, no. 2 (1968), p

34. [40] To make the story complete,

several of the Visa Paintings were

actually sold to the Oslo Plaza Hotel

after Nicolaisen, wearing his most

business-like suit, arrived at the hotel

director’s office with the pictures under

his arm.