INNER AND OUTER FACES OF TERJE NICOLAISEN was written by Kjetil Røed for the publication No More Jokes (2019) released on Kerber Verlag

INNER AND OUTER FACES OF TERJE NICOLAISEN

Kjetil Røed

”The face is not just an image, but also produces other images.”

Hans Belting, Face and Mask: A Double History. 1

“What then is our face if not a ’citation’?”

Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs. 2

As I flip back and forth through No More Jokes, it is the frailty of the faces’ exteriors that strikes me the hardest. Terje Nicolaisen maps out different characters and their surroundings, in a way that touches directly on who the portrayed in the deepest sense are. Not as a concluding description, not as a list of qualities, but by emphasizing that we are in need of something else than what we have become

accustomed to if we are to understand the individual human being.

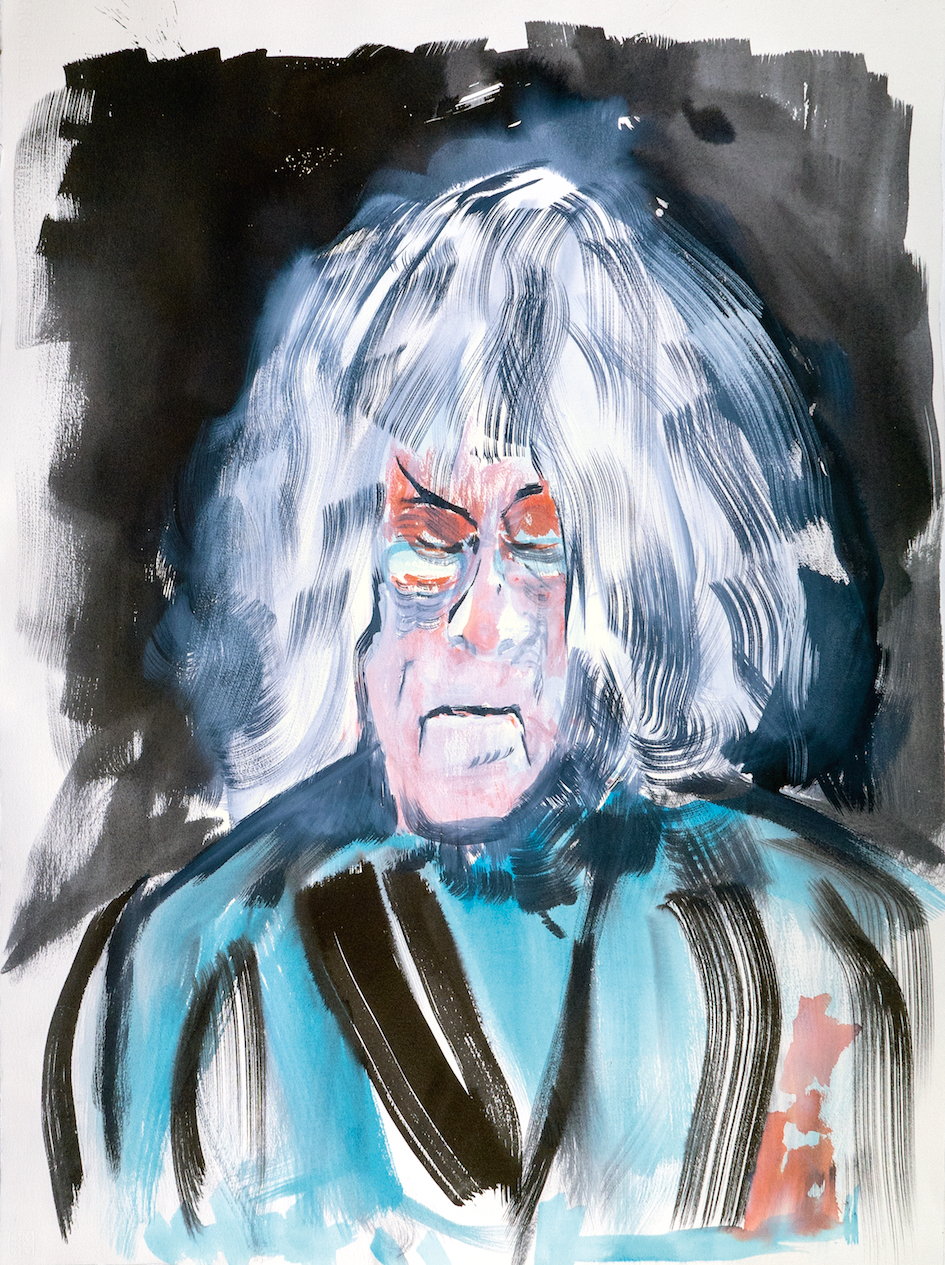

In Nicolaisen’s Dag Solstad (2017), the author’s hair gets a wild life of its own – it resembles a waterfall or an expressive landslide of white, flipping the portrayed out of the stabilizing author persona that is usually communicated through images of him. His face is porous, airy and saturated by other forces than the coordinates that keep “Dag Solstad” visually in place as a public figure that we recognize and know. In Virginia Woolf (with fold) (2007), the famous author’s face is about to disintegrate from within: her skin color is consumed by signal yellow, and shadows and hair accessories grow into moss-like dots or waterlogged sponge formations, which, together, drag Woolf out of the generic format that frames her authorship in a fine-tuned gravity and a delicate, strong beauty.

Nicolaisen’s picture of the author and protofeminist unlocks a repertoire of forces behind Woolf’s habitual surface, which actively works on the outline of the face’s relationship to the actual person and pulls her in different directions. For example, we can consider the portrait as something that has been dragged into natural processes about to consume the image: as if humidity and mould are just behind the frayed paper surface for in the next instance to sprout through and absorb Woolf’s appearance. In both instances – with both Solstad and Woolf – pressure is put on the symbolic value of the recognized, familiar faces of the authors. It is about unlocking famous portraits that have been locked into a pose or idea, or even make the face a scene of visual experimentation and reflection.

The identities of the people we are introduced to in No More Jokes play out in the artwork itself, as Nicolaisen attempts to locate the concealed asymmetries or points of disintegration that enable him

to reinvent our gaze on the people we encounter. The works are optical laboratories, where the purpose is not to achieve precise likeness but to make the artwork a site to contemplate who someone is. The paper becomes a stage. The color bleeds or shines a light through the lines, creating an unruly pulse or bursting line, so that the open shapes of the faces and sprawling outlines of the bodies awake a curiosity that will not be satisfied. I like that this identity matter is not rooted in characteristic features, recognizable gestures or well-known mimics, but vice versa: by releasing elements that move the face out of position as something representative.

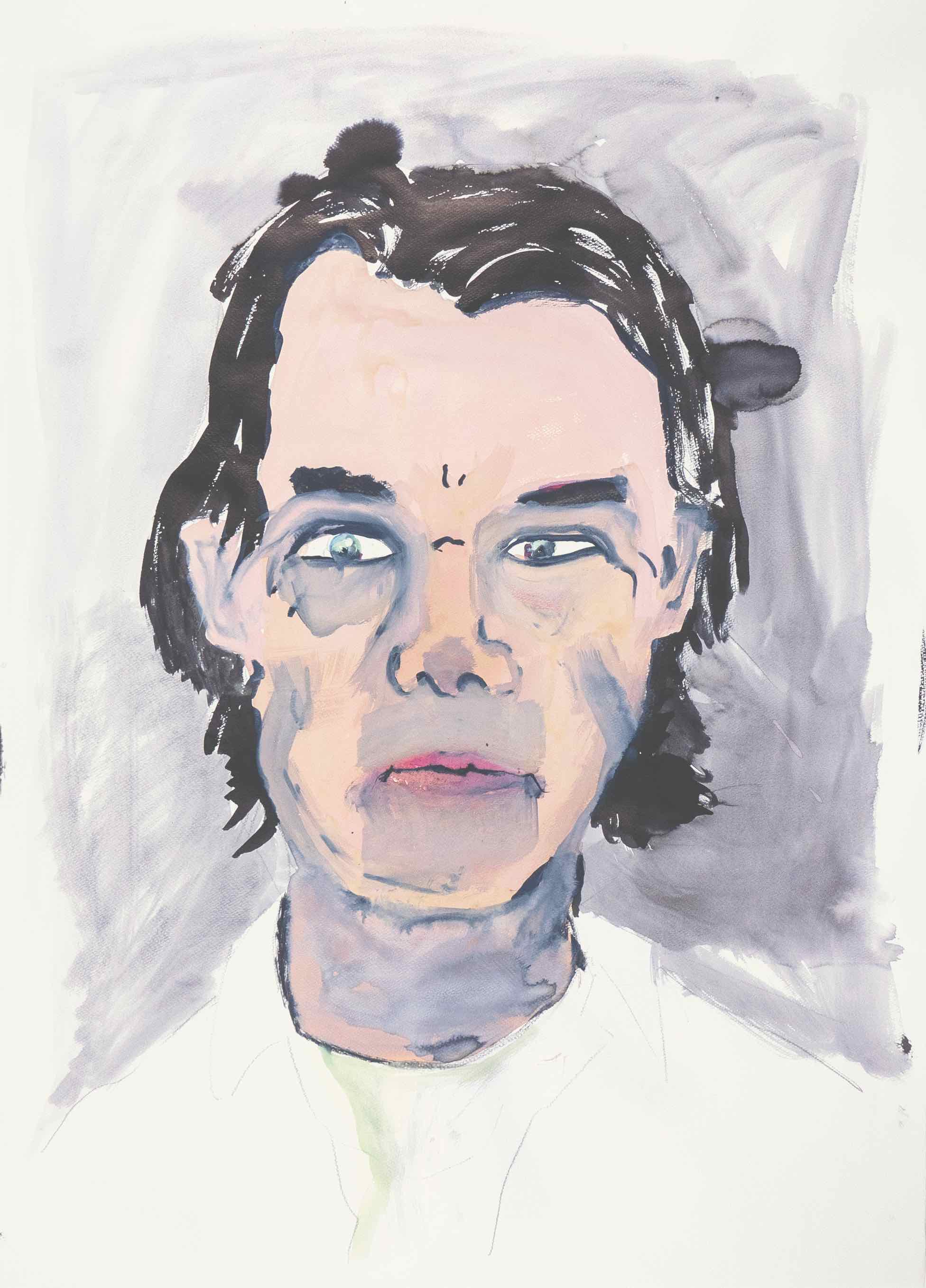

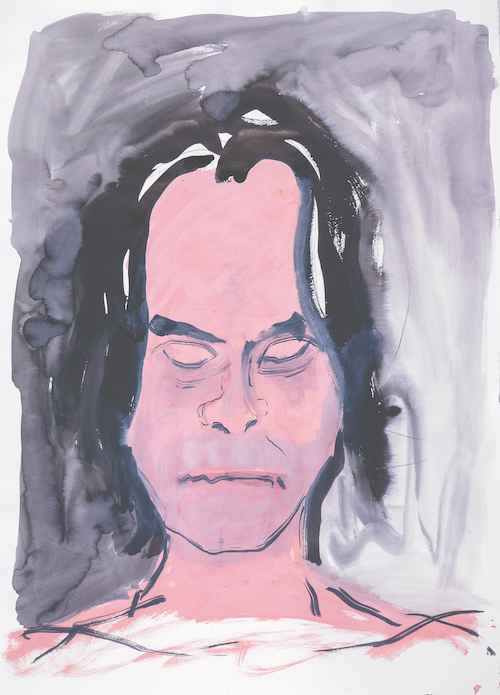

There is a sensitivity to these drawings that stimulates the curiosity about what the relationship between a human being and its face really is. In this way, Nicolaisen also creates a scene to experiment with different dramas to clarify his own identity. When we see authors and artists, it is namely often the artist’s own face that, directly or indirectly, lies underneath the other’s traits. This is seen most clearly in the works where the face doubles like two identity-bearing masks, literally pushed on top of each other, like in Dale Cooper (self-portrait) (2018) and Dale Cooper (self-portrait doppelgänger) (2018). The artist has placed his own face on top of Dale Cooper’s doppelgänger, that is, a doubling of a figure that already connects two faces, since Cooper in Twin Peaks is personified by the actor Kyle MacLachlan. This multiplication of both Nicolaisen and Cooper does not lead us to similarities between the artist and actor (or character), but rather a Janus face that is pulled in different directions by identities without clear markers, since we cannot pinpoint exactly where one face begins and the other ends. These are poly-portraits, where it veritably seethes in the visual tension the faces have ended up in. To force something together that cannot be reconciled keeps the elements open and initiates reflection on who the individuals are, based on how they appear.

But when are the masks on and when are they off? Is there a difference at all? We like to think that the face is the most genuine form of expression (the medium) to convey who we are. And it reveals something about us, no matter if we want it to or not: it is the body’s archival system, a biographical tachograph. Our life stories modify the flesh by making an entry of events and repeated mimics, like narrative marks on the face (wrinkles, sagging skin, scars, bruises, and so on). The mask, on the contrary, is something that we put on – something false and simulated, but also frozen in one expression. Therefore, we are not identical with the mask, it is something external, a shell without obligations because it is not us, although it reveals something general about human beings through its stylized features. It is not individualized, but a materialization of typologies, general emotional states like grief and happiness. Typologies are a shortcut to the defining states of human life, but they can also, which Nicolaisen demonstrates in this book, be used as a starting point for further processing and review of a particular face.

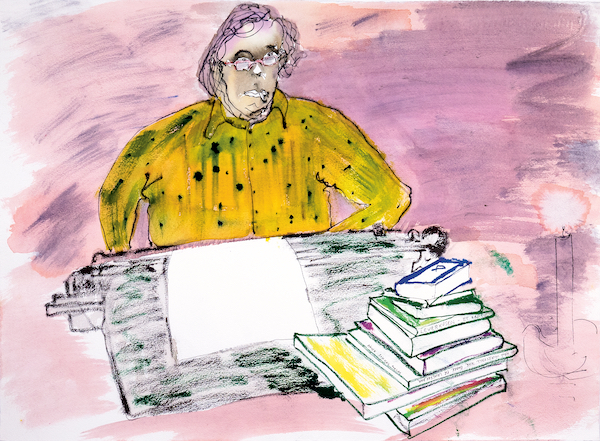

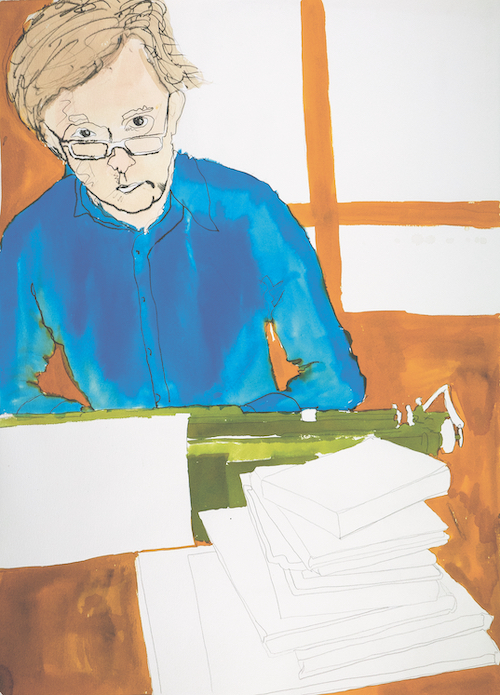

Just look at Nicolaisen’s portraits of himself as a writer: the reflective posture behind the desk with the obligatory disheveled hair and aslant cigarette and an analogue typewriter in the foreground, which places the production in a media-technological past, a couple of decades (or more) ago, when the “writer” was purer and still untarnished by the digital age’s Facebook procrastination and word processing’s promiscuous copy-paste writing. This is the author as myth but also as citation. In Empire of Signs, the French philosopher Roland Barthes speaks of the experience of seeing his own face reproduced in a Japanese newspaper: it was “japanified”, his “eyes elongated, pupils blackened by Nipponese typography.” 3 Shown on the facing page is the Japanese actor Tetsuro Tanba, originally published in the Japanese newspaper Kobe Shinbun, posing tough and brashly, an attitude that, according to Barthes, cites the Western actor Anthony Perkins’ characteristic mimics. In the reproduction, “he has lost his Asiatic eyes. What then is our face if not a citation?” 4, asks Barthes. We could answer him using Nicolaisen’s drawings, which show us that the unresolved state between individualizing faces and the mask’s citation can be left open, so that the transitions between them remain at a standstill, in a tension that cannot be resolved as one thing or the other. Barthes’ reflections on the body, face and identity are interesting in this context, as he tries to liberate himself from the closed relationship between them.

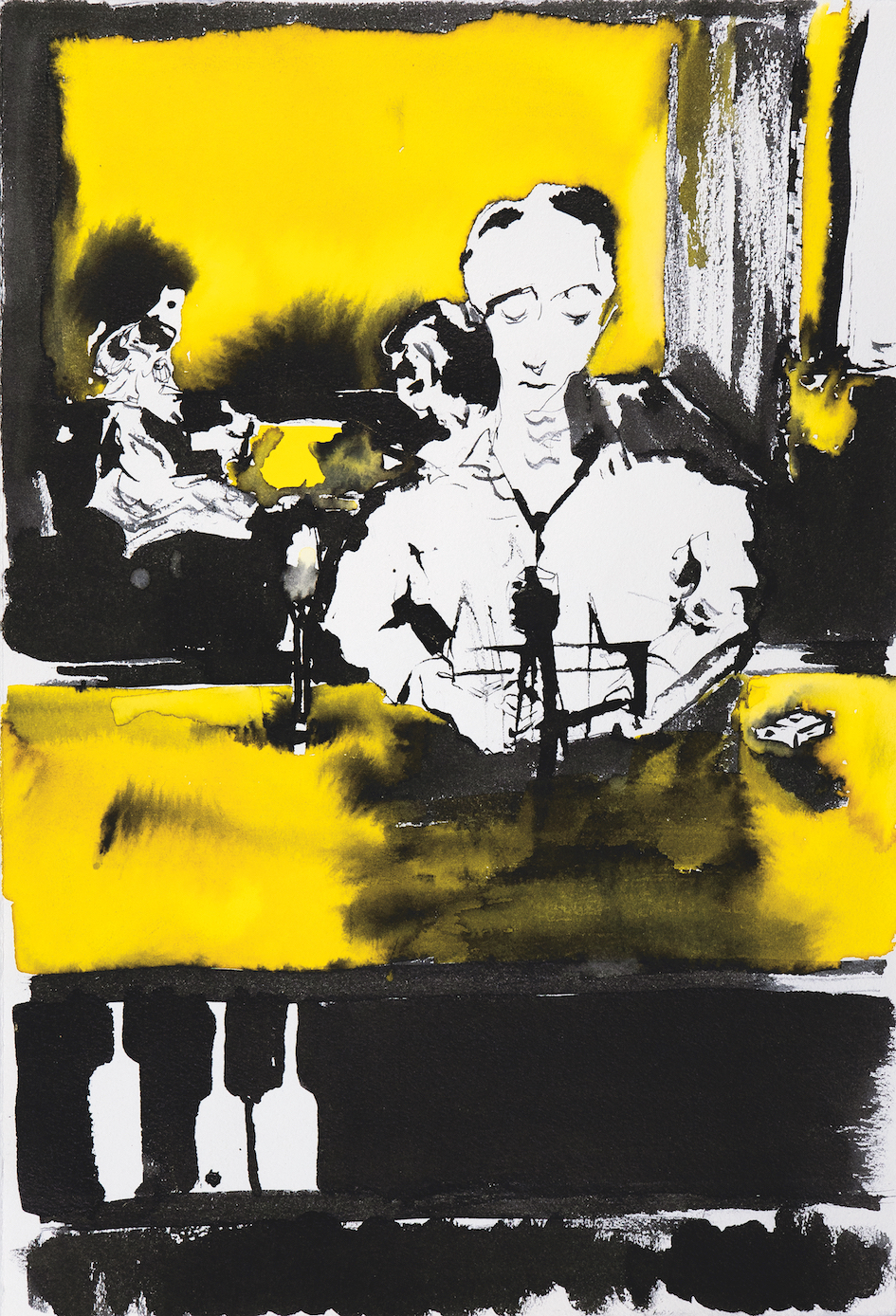

The artist’s staging of himself in At The Bar (2018) – where he looks like, exactly, Barthes (a citation?) – repeats another typology (the bohemian), but is modified by the visual sincerity of the face and body. The figure has cracks and slits and is characterized by a slope that prises the scene open, so that the figure’s pose fails in keeping the portrayed artist inside the drama he is depicted in. There are fluffy shapes in the background, which, due to the watercolor, bring both the characters and the interior behind the protagonist into a fluid state. Yet again, I cannot help but think that this dissolution of the face and the place’s solidity has to do with forces that threaten or destabilize the place and people’s identity – that the protagonist does not entirely believe in the role he has taken on, or that the people behind him, perhaps, would like to throw off their refined selves as cafe patrons and rather take their clothes off and scream. Any such scene is but a coating on various forces, wishes and conditions that at all times threaten to disperse the drama and the roles’ fine outlines. Here, the shape itself touches on these destabilizing forces, they tear and toil on what comes into view, thus enabling us to think about the underlying unrest. Perhaps one could say that Nicolaisen liberates the face from the bodily unity that the West, according to Barthes, views the individual through? Mimics and gestures break free from the idea that we will see a particular person, without Nicolaisen sacrificing the composition’s premise: The wish to know who we are looking at.

Again, I flip back and forth through Nicolaisen’s watercolors and drawings and think that what was supposed to be a representation of something – a face, a body, a situation – is in this book, a visual adaptation that does not mind showing the faceless chaos directly – the disorder that threatens any external expression of identity with the loss of control, death, illness or decay. The terminal point for the conflict between the face and the faceless is found in the works that strip off the face’s patina to reveal the shapeless flesh underneath. In My People (2000), Summer Darkness (2005) and especially Untitled (careless whisper) (2003), it is as if not only the mask but the face itself is gone. The cited face has been pushed aside to the benefit of the forces an organized face usually has under control. Like the painter Francis Bacon so clearly showed us, it is the impersonal flesh that we hide behind the mask, which, like a civilizing coulisse, covers what we share with animals. The violence that rises in the pictures is as disturbing as Bacon’s, since Nicolaisen shows the madness behind the mask, unveiled, both in this book and everywhere else. It is especially the fleshy and brutal chaos that gapes towards me in Untitled (careless whisper) that seizes me with its intensity, but at the same time I wonder if the work refers to a song by George Michael that I cannot stand. I dig out the lyrics, which without Michael’s placating honeyed voice surprises me by instead empowering the brutality opened up by the flesh unfolding in front of me. The depiction of lost love tells me that whispering is inconsiderate, as it conceals infidelity with fake sympathy. The mouth’s crooked whisper in Nicolaisen’s drawing still takes it a radical step further, being robbed of human refinement. He (or she) can no longer control the application that becomes entwined in a whirl of flesh, where the faceless underneath punctures all order.

It is evening and once again it is snowing outside my office windows. Inside, in the heat by the desk, I cannot stop looking at Nicolaisen’s drawings. They tug at the masks I wear myself and if there is something they make visible, it is how frayed our faces often are. At the same time, fortunately, he says that it is easier to find a face with long-lastingness when we become aware of its frailty. It is about being sincere and overtly curious about oneself and others. Just like Nicolaisen is in this book.

1 Hans Belting: Face and Mask: A Double History, Princeton

University Press, 2017.

2 Roland Barthes: Empire of Signs, Hill and Wang, The Noonday

Press, 1982.

3 ibid.

4 ibid.